Rediscovering Scarcity, Chapter 1

When Intelligence and Money Break: The Dual Singularities Ahead

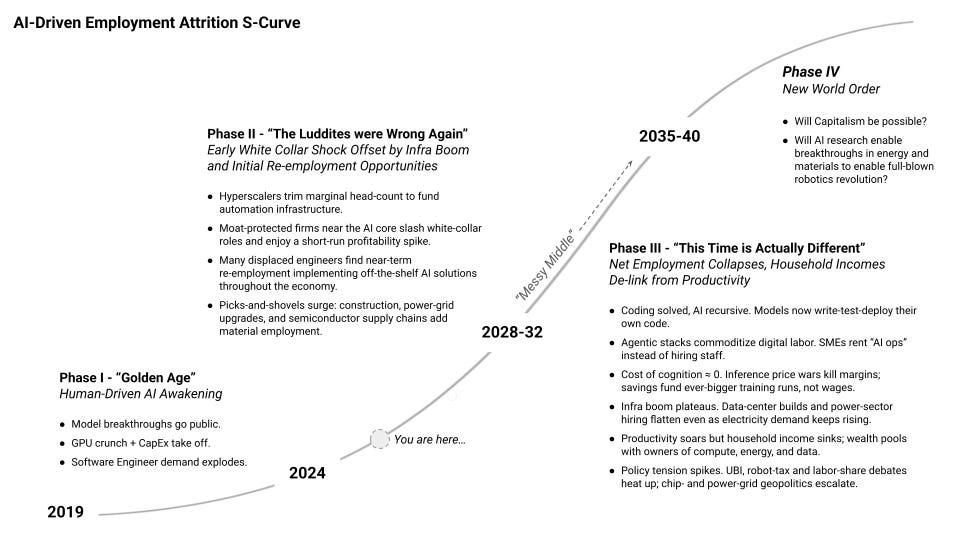

The following outlines what we see as the most likely path for the coming decade. Our aim is not to be precise nor to provoke, but to be ready. Consider this a projection of structural, technological, and macroeconomic forces already in motion, shaped by today’s constraints on capital, energy, and human adaptation. Other paths remain possible, of course, including low-probability outcomes such as a sudden recursive takeoff to AGI or an unforeseen geopolitical shock that reshapes the cycle entirely.

Here are our key claims:

Monetary Singularity before AI Singularity. A fracture in the dollar reserve system and a rapid shift toward adversarial geopolitical blocs will precede the AI Singularity. Debt crunch, accelerated money printing, and inflation arrive first and shape everything that follows.

Monetary Singularity = the moment it becomes clear we are irreversibly shifting from a paper-money (currently US dollar) global reserve system to one ‘backed’ with hard money(s).

AI Singularity, by our definition = inflection point where AI economic diffusion enters the steep phase of S-curve.

Economic Diffusion = the process through which technical capability becomes productivity, profits, and adoption.

AI stocks will crash before the Monetary Singularity. Current AI is amazing but cannot diffuse economically. The AI investment cycle will break: capex overbuild collides with AI revenue chasm and scarce inputs. Ramifications will help accelerate us towards Monetary Singularity.

Nonetheless, AI will end up irreversibly destroying net jobs and forcing a wholesale reset of today’s managed capitalism. AGI is not necessary for highly disruptive economic diffusion. In fact, the hyperscaler obsession with AGI is an impediment. After the AI bust, hyperscalars will pivot to applied automation causing output to decouple from wages. Our model projects ≈10% unemployment by 2031, worsening thereafter absent regulatory intervention.

AGI = Artificial General Intelligence, an AI that matches or surpasses humans across most cognitive tasks: able to learn, reason, and generalize across domains without task-specific retraining.

With AI now treated as strategic infrastructure, intensifying U.S.-China rivalry and rapid aging in advanced economies will override anti-tech populism, delaying meaningful policy reaction.

Practical economic AI diffusion, not bigger frontier models, may be the fastest path to AGI anyway. Real-world deployment, live feedback loops, and constraint-aware engineering might build generality better than training even bigger models that “reads the whole internet.”

Goodbye 60% S&P 500 / 40% U.S. bonds portfolio autopilot. After 45 years, the Pax Americana disinflation playbook is over. Only active, macro regime-aware managers who find scarcity amid cheapening intelligence, and thinning Big Tech moats, will earn excess returns.

Table of Contents

Scarcity Fund Macro View for Next Decade

The AI Diffusion Gap: AI Is Superhuman, But Somehow not that Useful

Today’s AI is an idiot savant. It’s able to help PhD mathematicians crack hard problems, but still not able to reliably run your Verizon call center end-to-end. That’s why economic diffusion remains far below expectations despite AI’s miraculous advances.

The Reckoning: Current AI Economics are not Even Close to Working

Unfortunately, broad economic diffusion, not quantum computation proofs, is where the revenue is. As this sinks in, expect an overcorrection: prices and sentiment whipsaw from AI Gilded Age to AI Autumn. Hyperscalers have burned through cash hoards. To keep funding AI infrastructure they’ll need to borrow or raise equity from an increasingly cynical investor base.

The Reflexive Shock: The Monetary Singularity Comes First

With AI capex propping up much of recent U.S. GDP growth, a pullback triggers layoffs across hyperscalers and suppliers, compressing spend and deepening the slowdown. The AGI-utopia storyline fades. Adoption grinds forward on sober, slower timelines (much like “net-zero carbon emissions” has slipped from everyone’s collective memory). Markets pivot completely to geopolitics and macro as recession-driven deficits bring us back to outsized money printing. Whether, when, and how the dollar system cracks becomes the dominant market narrative. The possible end of the Anglo-American hegemon (a few times per millennium event) becomes the only singularity on everyone’s mind. We shift from scarce compute assets to scarce hard money.

AGI is Optional: Diffusion Becomes the Business Model

The AI ecosystem sidelines AGI and doubles down on revenue-driven diffusion, finishing “single-player” analyst/coder use cases, then starting to grind through multi-stakeholder, cross-system workflows. Despite ugly sentiment, development continues underneath the radar. Knowledge-work employment erodes on an accelerating curve while most pretend not to notice.

Jobs Suddenly Start Disappearing: The Noticing Comes too Late

As monetary stimulus pulls the economy out of recession, it will become clear the lost jobs aren’t coming back, not even at the 2010s’ sluggish pace. Policymakers will be slow to react, treating AI as strategic infrastructure in a U.S./EU–China/Russia/BRICS contest amid fast-aging populations. Once key diffusion bottlenecks are solved, automation will bite harder into employment until populist pressure, and eventually regulators, move to deliberately slow the rollout.

Investor Note

Methodology: Scarcity Fund Employment Model

Disclaimers

References

1. The AI Diffusion Gap: AI Is Superhuman, But Somehow not that Useful

Most opinions fall into one of two camps: “AGI will be everywhere soon” or “AI is just another tool.” The reality is more nuanced.

AI is already far more capable than most people think on high-complexity, bounded tasks. LLMs are superhuman interpolators of dense knowledge encoded in their training. The evidence is clear:

Anecdotal

Math: Elite researchers use frontier models to probe lemmas, generate counterexamples, and accelerate proofs.

Code: AI-authored routines are landing in core libraries. AI assistants refactor and test at scale.

Material Science: AI collapses millions of candidates to a short, synthesizable list for lab work.

Weather: ML systems outperform standard 10-day baselines on key accuracy metrics.

Legal ops: For narrow templates (NDAs, MSAs), AI first drafts and redlines are reliably solid. Attorneys can focus only on bespoke clauses.

Economic Data

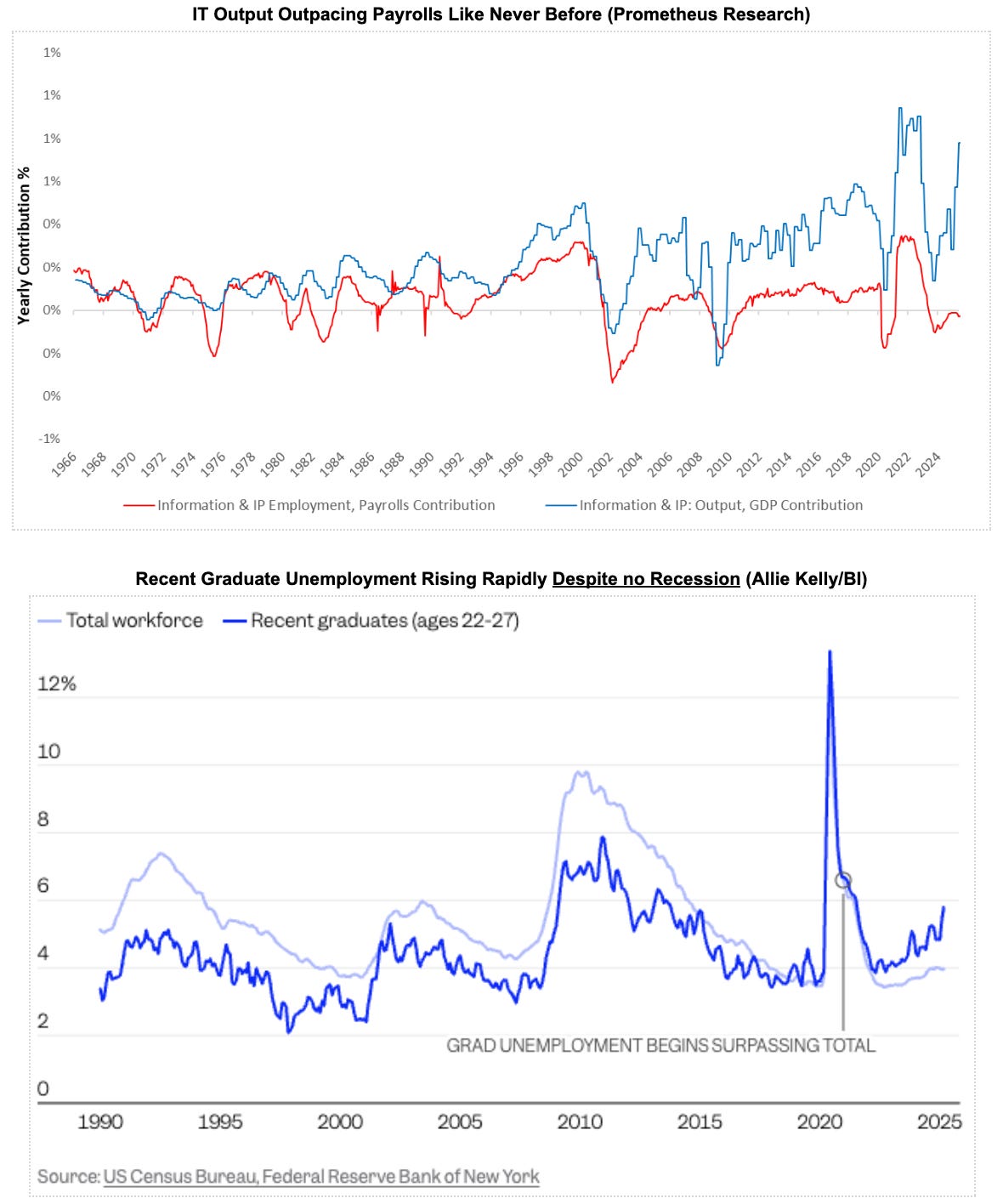

Productivity gains are concentrated in software/IT

Recent knowledge grads face record unemployment outside recessions

Firms with lots of bounded complex work, like drug1 and finance companies, are cutting the most headcount2

By contrast, AI diffuses far more slowly than people expect across the broader economy wherever workflows are messy and unstructured: high complexity, frequent hand-offs, and cross-division coordination - i.e., unbounded tasks. This makes sense because generating value requires bottom-up org re-architecture, workflow redesign, and heavy data plumbing. These things are all done by scarce tech and design talent operating against entrenched habits and incentives. Here, the evidence is still a bit opaque, but rapidly mounting:

Anecdotal

~95% of large-company deployments stall3

~30% of 2024 corporate gen AI proofs of concept are likely to be abandoned in 20254

Stubborn hallucination liability persists. Customer-facing copilots often pulled after a few high-visibility errors. Legal/compliance won’t sign off without tight guardrails.5

Model drift and ownership challenging operations. Nobody “owns” post-deployment retraining, performance decays, and business turns the system off.6

Economic Data

AI revenue remains absolutely miniscule relative to the capital already committed

Below is our framework on bounded versus unbounded tasks (see links in references)7:

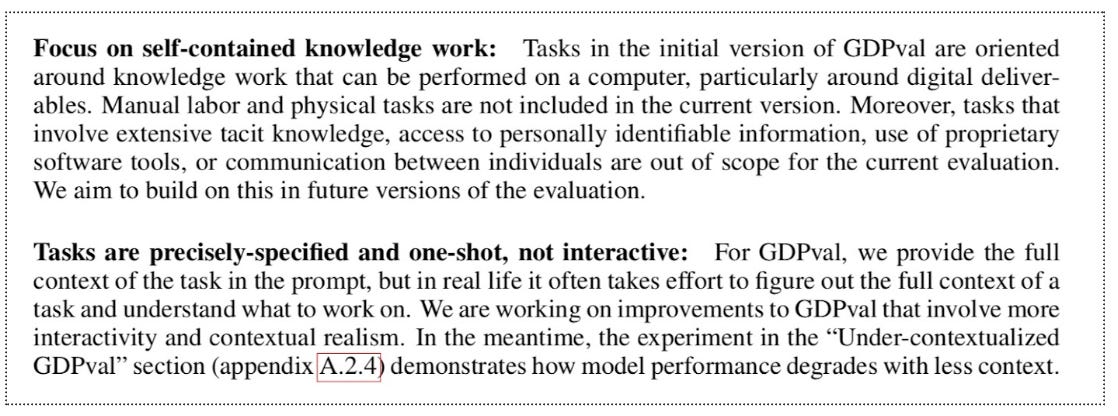

Insiders see firsthand that broad AI diffusion is stymied by structural obstacles. The shortcomings in OpenAI’s recent framework on AI’s impact on economic activity and tasks are telling (OpenAI GDPEval)8:

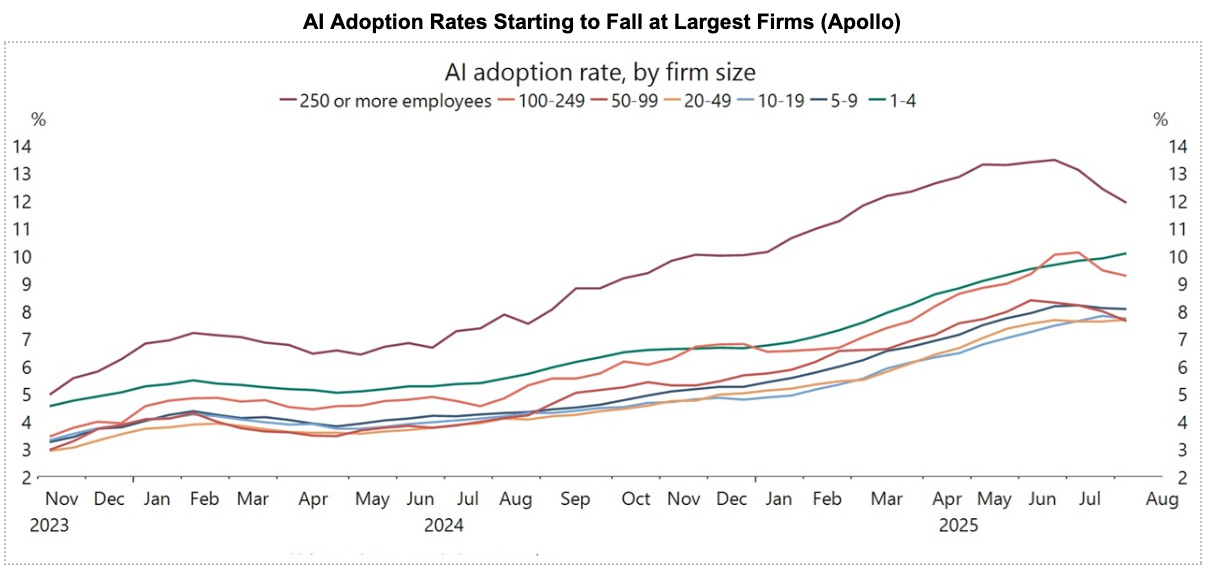

The impact of this dichotomy is that, for the foreseeable future, AI will continue to deliver incredible and surprising results on bounded, highly complex problems, but will fail to achieve mass adoption on the more banal but unbounded activities in the economy. Unfortunately, this is most of what humans do, and hence, where the real money is. A recent Apollo study indicates that AI diffusion may not be ready for prime time9:

Therefore, the big near-term question for AI’s real-world impact is whether today’s unbounded tasks can be recast into clear, bounded steps. Two recent papers point to possible new paths. Firstly, train agents to build general-purpose “world models” and judge them by whether their skills carry over to new but related situations, not just by turning up model size or rewards.10 In parallel, build the context plumbing (the data pipes and memory that gather, organize, and deliver the right information at the right moment) so outputs slot cleanly into real workflows.11 We’re agnostic about which specific tools will ultimately win, but confident smart engineers will figure it out.

2. The Reckoning: Current AI Economics are not Even Close to Working

A tail of two AI booms - investment dwarfs revenues:

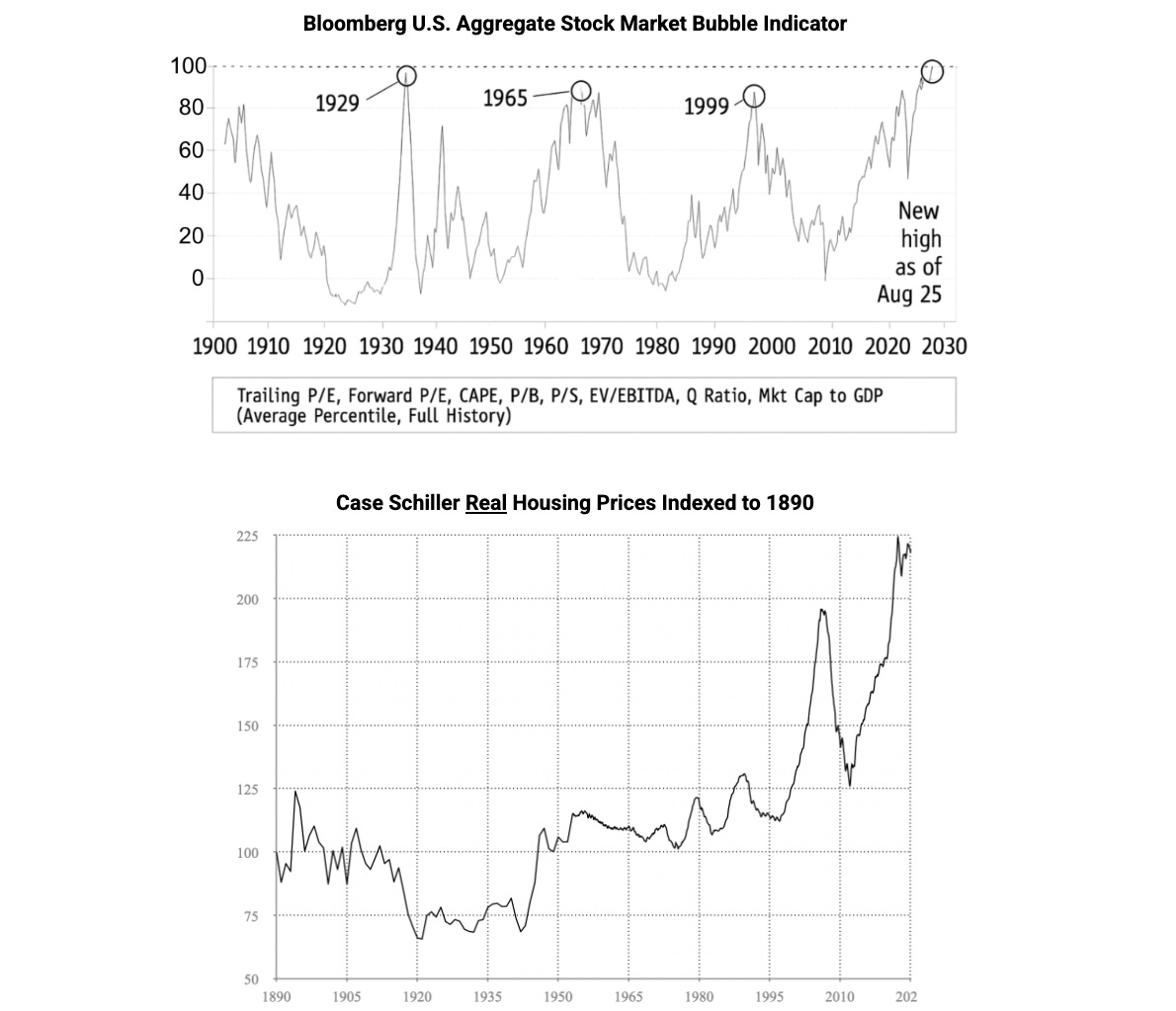

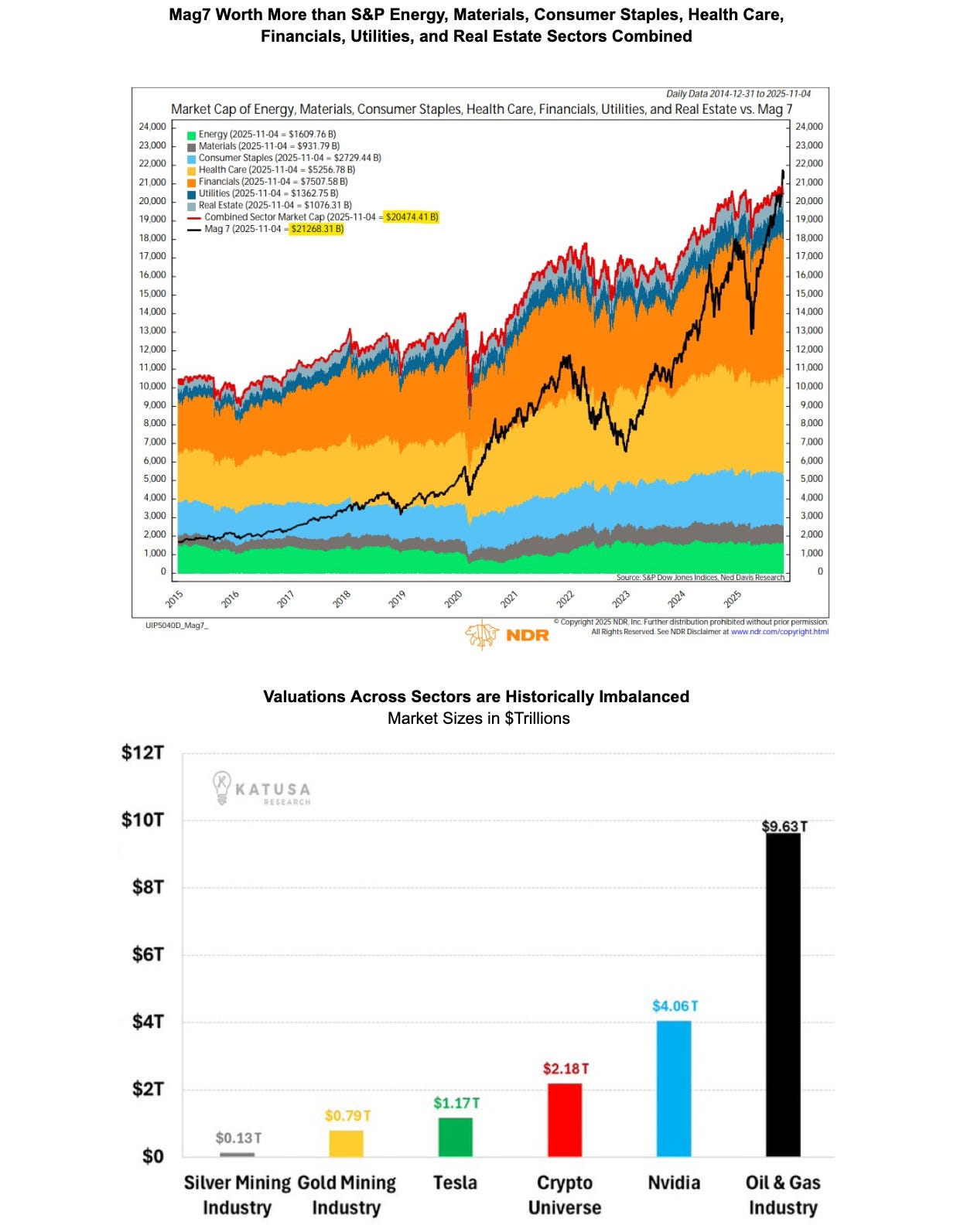

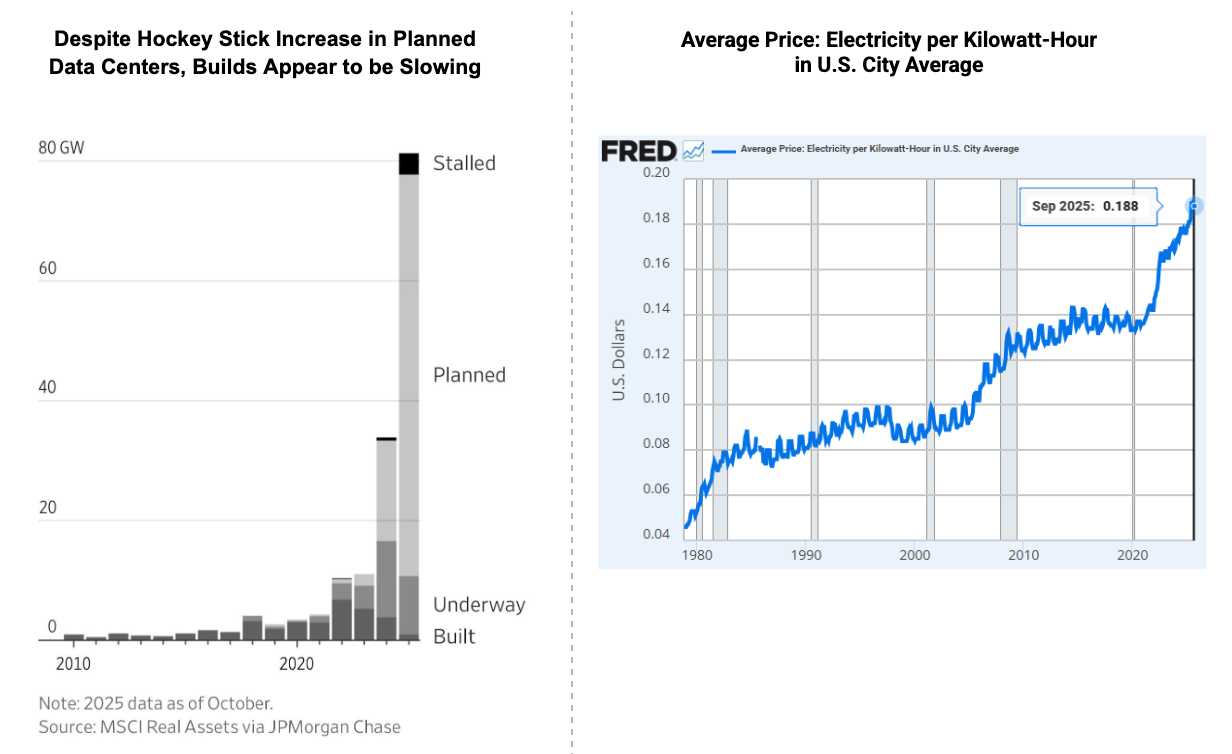

On one hand we have promises of 20% AI capex CAGRs through 2030, steadily growing 401ks forevermore, and new AI innovations seemingly every day. On the other hand, AI-related capex is ~100% of GDP growth12 (like broadband in 1999), electricity costs are up 50% in many areas13, stock valuations are at bubble levels by almost any indicator, and yet simple math shows that AI revenues (not profits) equal << 5% of the infrastructure spend powering them. In the meantime, the commodity squeeze is real: frontier model training is fleeing the overloaded grid, only to slam into multi-year backlogs for turbines and core datacenter kit off grid.

The below charts clearly paint the picture of an unsustainable business14:

Accounting makes earnings look much higher than they are:

Vendors (nVidia chips, Eaton power, Vertiv cooling) book revenue immediately. Buyers, on the other hand, capitalize capex and stretch depreciation (~6 years for servers/networking; ~7–40 for buildings15) for GAAP accounting, while accelerating deductions for tax under the “Big Beautiful Bill” (100% bonus depreciation for qualified assets16). Net effect: expense recognition is deferred in earnings but accelerated for taxes, so reported profitability looks sturdy even as free cash flow craters. The ecosystem’s earnings appear to rise exponentially in the aggregate while the underlying cash economics rapidly deteriorate. The stark reality: OpenAI is one of the biggest cash burning furnaces in history. Microsoft’s Sept-30 quarter filing implies OpenAI posted a net loss of about $11.5B in that quarter. If sustained, that equates to an annualized loss run rate of roughly $46B, though a single quarter may include one-offs17.

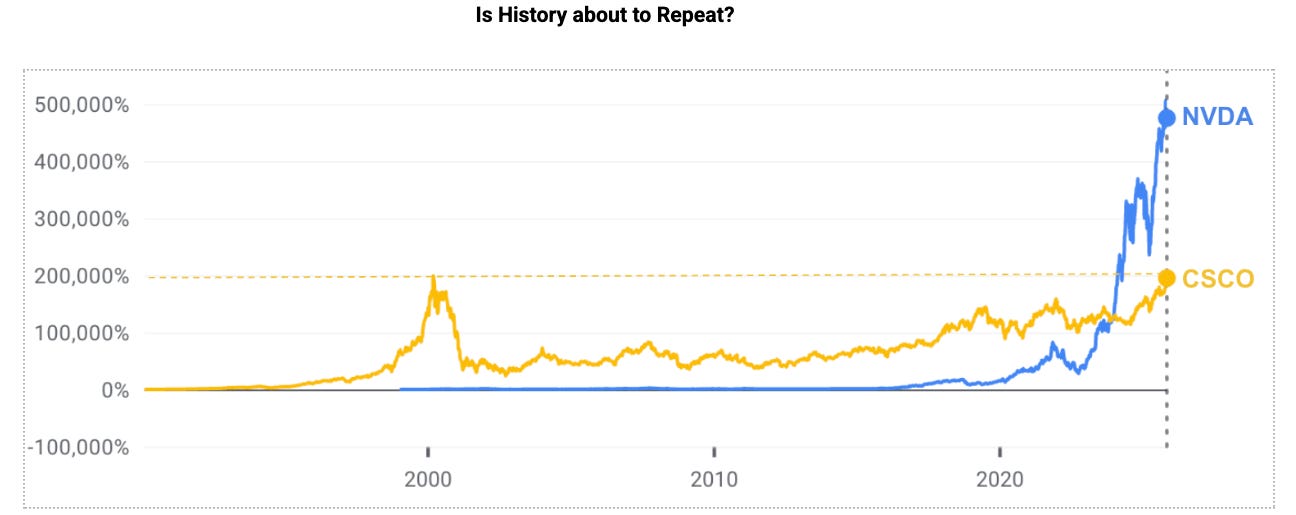

There are many other similarities to 1999:

Telecoms laid fiber before demand. Cisco, the nVidia of the internet boom, is only now back to the market valuation it achieved in 2000.18

1999 ended with bandwidth oversupply. 2026–28 could see pockets of compute/power capacity that can’t be priced to hurdle rates. As can be seen below19, IT investment has reached 1999 levels.

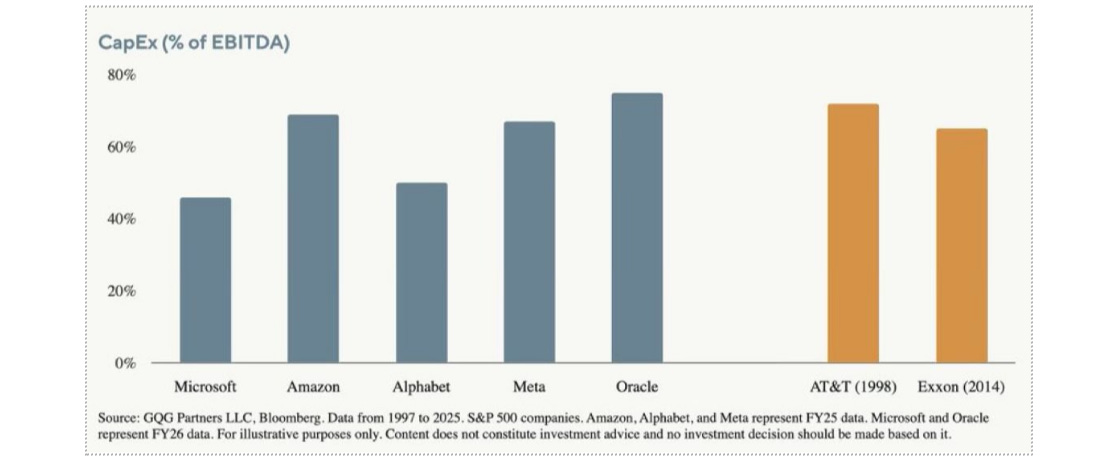

ISPs struggled to charge for the value created. Hyperscalers risk utility-like multiples if customers won’t pay for AI’s surplus (or if the profits accrue to other players). They look more and more like asset-heavy commodity providers as can be seen below20:

This is causing a funding crisis to slowly emerge21:

This timing mismatch between AI economic diffusion and the deployment of infrastructure capex is pushing AI funding perilously up the risk curve. When hot financing runs out, debt issuance will be the only place left to keep the flywheel going22. The “grow-into-the-spend” story looks untenable. Revenues won’t arrive fast enough to close the funding gap, and OpenAI’s recent turn toward “erotic content” and ad revenue reads like tacit admission. Over the next 6–24 months, this reality is likely to become common knowledge and the group will re-rate.

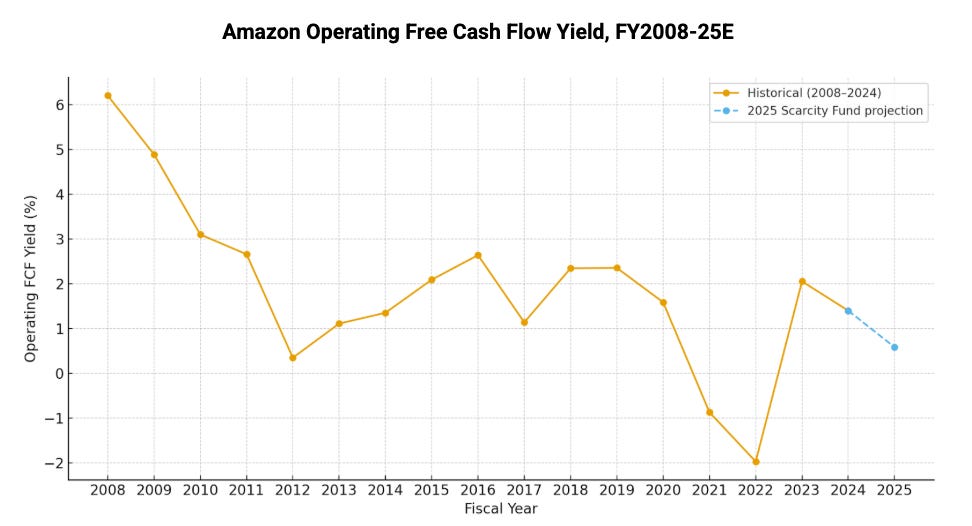

Wave 1 — Flush balance sheets: Hyperscalers funded ~$0.5T from cash hoards they had built up over decades. Now GOOGL/MSFT/META have only ~$150B combined net cash left23. By our estimates, 2025 FCF yields for the group will fall to ~50% below 2020.

Wave 2 — Venture capital: ~70% of venture dollars chasing AI, an unprecedented single-theme concentration24. SoftBank-style behavior is back: mega-rounds, structured secondaries, and NAV lending that extend runway while amplifying cyclicality.

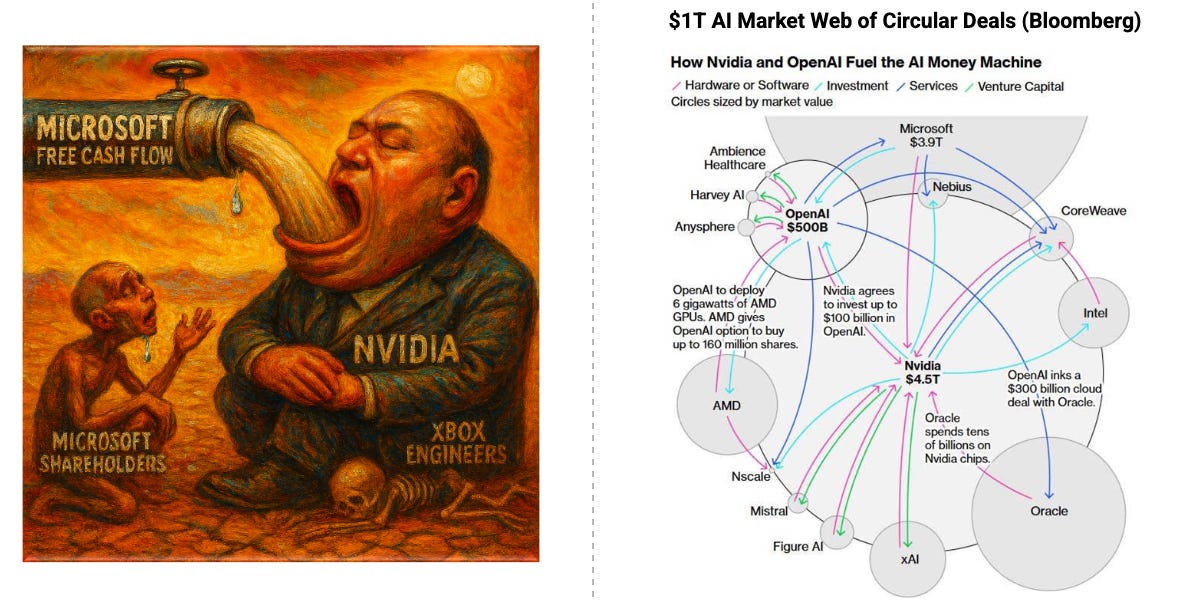

Wave 3 — Supplier finance (now equity-linked): Prepayments, vendor credits, take-or-pay/capacity reservations, and suppliers taking equity in customers in exchange for demand. nVidia began the trend by extending credit to its largest customer, OpenAI. Once companies saw that share prices surged on deal announcements, the model metastasized across the ecosystem. Equipment vendors and component suppliers, eager to keep the flywheel spinning, are taking equity stakes in their customers, purchasing shares or convertible instruments whose rising valuations then feed back into their own reported gains. Accounting revenues rise, balance sheets swell with “strategic investments,” and the entire system finances itself on paper gains. In the meantime insiders are liquidating their inflated stock at record speed (nearly 80% of nVidia employees are now paper millionaires25). In this way, vendor financing becomes the final, most deceptive form of equity financing: a circular system that channels retail capital into AI capex under the illusion of endless growth.

Wave 4 — Debt: More private credit, converts, ABS/project finance. Oracle’s recent $38 billion debt package, the largest ever tied to data-center financing, illustrates how far the leverage cycle has advanced. The company had already raised roughly $18 billion earlier in the year, and analysts now estimate it may need to borrow up to $100 billion over the next four years to meet its AI infrastructure commitments26. Meanwhile, Oracle’s credit risk premia have ticked up: its 4.9% Feb-2033 notes widened to ~100 bps OAS in November. Borrowing is exploding generally27:

Wave 5 — Government Support: Debt guarantees and direct subsidies. On November 5, 2025, OpenAI’s CFO appeared to signal that the company might seek U.S. government guarantees to lower the cost of financing AI chips, effectively a credit backstop that would shift downside risk to taxpayers28. The next day, Sam Altman tried to draw a line, asking: “Is OpenAI trying to become too big to fail, and should the government pick winners and losers? Our answer on this is an unequivocal no.” Yet he also acknowledged that “OpenAI has spoken with the U.S. government about the possibility of federal loan guarantees to spur construction of chip factories in the U.S., but has not sought U.S. government guarantees for building its data centers.”29 If and when AI stocks correct, we expect this tension to become acute. Policymakers will face a real choice: allow the market to clear, or subsidize continued infrastructure spending on national-security grounds.

As of the writing of this chapter (Q4 2025), we’re seeing growing cracks in the AI-capex narrative and are likely entering a significant market correction (although not necessarily the crash), particularly in the semiconductor space.

Meta = visible cracks: beat on revenue and EPS but the stock fell ~11% after guiding to higher capex, reinforcing its status as the worst AI exposure (no frontier model and billions already burned on the metaverse common knowledge failure30).

Amazon = earnings beat leaned on a $9.5B non-cash Anthropic mark-to-market. Critics also flag possible “round-tripping” (funding Anthropic with cash/credits that return as AWS revenue). Despite ongoing FCF compression shares rose ~12% post earnings but have recently sold off significantly.

CoreWeave = Strong Q3 beat but tempered guidance led to 16% post-earnings dump. However, guidance trimmed after a third-party data-center “powered-shell” delay slowed capacity handoff to a single customer31. CoreWeave is a specialized GPU cloud purpose-built infrastructure that rents nVidia-class compute for AI training and inference. It therefore is a canary for aggregate hyperscalar demand.

nVidia = massive beat on revenue and earnings but with some questions around quality (inventories grew 10% faster than sales QoQ). nVidia initially rallied up to 7% post market before crashing back down to roughly 15% below its peak value. This is likely the result of technical exhaustion and rate cut jitters.

3. The Reflexive Shock: The Monetary Singularity Comes First

Every great boom ends the same way: under the weight of its own reflexivity. The AI build-out has been both the cause and the consequence of recent GDP strength, a self-reinforcing cycle in which capex fuels growth, and growth justifies ever more capex. But when revenues fail to materialize and balance sheets begin to strain, that feedback loop turns vicious. And this reversal will unfold amidst one of the most overvalued equity and real-estate markets in history32.

There is, however, a crucial caveat: overvaluation can grow far worse before the reckoning arrives. The Fed is easing into an asset bubble even as inflation remains roughly 50% above target. In past bubbles, the central bank was tightening aggressively, but today, it cannot. As we will show later, U.S. sovereign debt levels no longer permit sustained tightenings. We are entering what Ludwig von Mises called a crack-up boom, the final, self-reinforcing stage of monetary debasement, when markets mistake nominal gains for real prosperity and speculation is required for survival. Asset prices rise not because confidence in the economy endures, but because confidence in the money is failing.

We can’t know which pin bursts the bubble. The list of plausible triggers is long and not mutually exclusive.

Inflation resurgence + K-shaped backlash33. Inflation re-accelerates while a K-shaped economy widens inequality, fueling populist pushback. ~82% of Americans live in regions already showing recessionary conditions despite an overall economy growing ~3.9% on Fed nowcasts (Nov 1, 2025). Sentiment is sliding while stocks keep rising. Policy hits a no-win constraint: keep monetizing and you intensify affordability pain for the median voter through inflation. Stop spending/printing and the equity market loses its liquidity bid.

Credit stress despite easy conditions (a la 2007). Even with aggressive spending and easy financial conditions, balance-sheet weak spots are starting to impact funding markets. Pockets of fraud and bad loans are emerging in private credit and the broader shadow-banking complex, and the “cockroaches”34 are showing up as a steady trickle of smaller bankruptcies. For now, the damage appears concentrated in subprime auto and commercial real estate35, and broad gauges like high-yield spreads remain relatively well-behaved. At the macro level, leverage and household strain look contained: business-plus-household debt is comparatively low versus GDP, and fixed-rate mortgages keep debt-service burdens near pre-pandemic levels.36

Terrible AI ROI for the Frontier Model providers becomes impossible to ignore. AI Revenues continue to stall despite enormous capex, eventually putting buybacks and dividends at risk at the publicly-traded companies. They are already frontrunning this economic reality with layoffs. Microsoft announced its cutting 7% of its workforce in May and July37. Amazon announced it’s cutting 14,000 corporate jobs in October.38

nVidia materially misses revenue or EPS despite seemingly parabolic AI-infra capex. This would signal either a slowdown in total spend or cracks in the current model. As the ecosystem’s dominant profit pool, an nVidia miss would call the broader AI trade into question. The charts below39 show the growing electricity bottleneck and that while planned data centers are balooning, built and underway data centers are leveling off:

Unexpected domestic event worsens U.S. balance sheet stress. COVID was the extreme case. A smaller example would be a Supreme Court ruling that voids tariff schedules, stripping customs-duty revenue and widening the deficit by ~1–1.5% unless offset by new taxes or spending cuts. With Congress gridlocked, that likely means heavier near-term issuance, a selloff in U.S. Treasuries, and tighter financial conditions. Justices have already signaled skepticism.40

Geopolitical shock. A low-probability, high-impact event (war, sanctions, US treasury sell off, critical-infrastructure hit) punctures risk appetite and liquidity. The snapshot below41 from Reuters shows the degree to which a hot war between NATO and Russia is proceeding. Russian energy assets 2,000 km from Ukraine have been hit. Notably, as of this writing, Russia has sent warships to Venezuela as a deterrent against a U.S. regime change campaign42. A re-opening of the Iran war that leads to actual oil-extraction (not just refinery) assets being hit is another possibility.

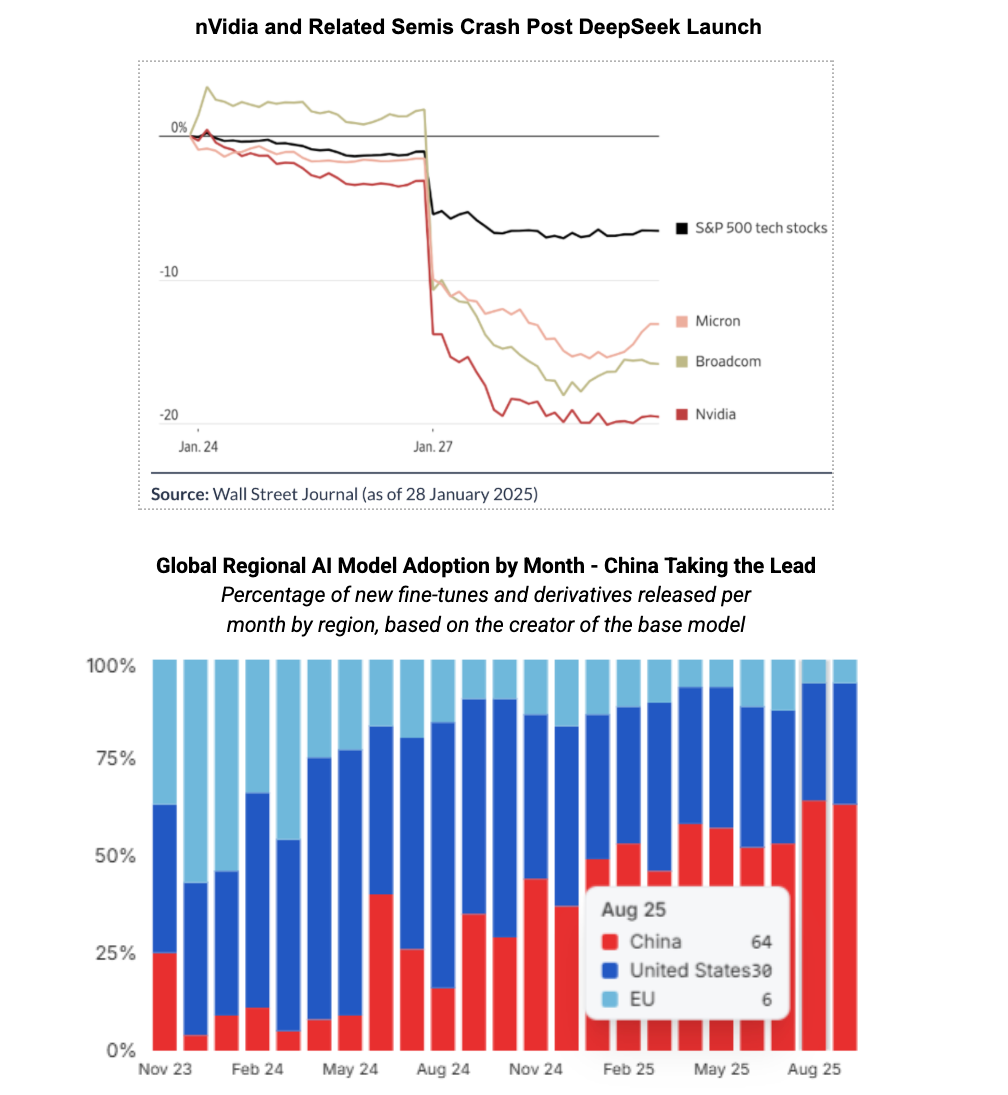

Another, more durable DeepSeek moment43. It becomes clear that Chinese models are competitive despite far lower investment. “Napsterization”: more generally it becomes common knowledge that frontier model IP cannot be ringfenced. When DeepSeek launched, nVidia lost 17% ($600 billion of market value) in 3 days.

Regardless of the catalyst, once equity market enthusiasm fades, the marginal dollar of AI capex funding will rapidly evaporate. Projects will be delayed, suppliers will scale back, and the downstream ecosystem (chipmakers, data-center builders, utilities) will quickly get hit by the shockwave. The pullback will cascade through the economy, amplifying weakness across sectors that no one thought had been buoyed by AI demand. This is the reflexive shock: falling investment cuts income and employment, which further dampens demand and confidence, tightening financial conditions precisely when they need to loosen. With AI capex having propped up much of U.S. growth, its reversal exposes how narrow the expansion really was. What looked like a productivity renaissance reveals itself as another capital-spending bubble. The macro consequences are stark. Aggregate earnings will finally reverse, tax receipts will plunge, and deficits (which are now 5-8% in periods of growth) will explode as U.S. interest costs continue to rise as cheap sovereign financing continues to roll over. Stock declines will trigger powerful negative wealth effects, pushing consumers into defensive retrenchment. Housing, already soft under the weight of high mortgage rates and lack of affordability, will roll over sharply. The private-credit bubble will begin to fracture, defaults will spike, and long-hidden frauds will surface in the usual end-of-cycle fashion. Policy response is predictable: restart the printing press. To arrest a credit spiral and stabilize assets, the Fed and Treasury will absorb a rising share of issuance, monetizing enormous recessionary deficits. That’s when the narrative flips: burned investors will pivot from AI euphoria to geopolitics and money. The focus shifts from an “AI singularity” to a monetary one, the cracking of the dollar order. The dollar’s store-of-value status and reserve privilege, global economic pillars since 1945, are already straining as can be seen in the charts below. As this accelerates, the market’s central question won’t be what AI can do, but what money is. We believe we have already passed the monetary event horizon and that a return to hard-money backing is inevitable44. Notably, all developed powers, including China, are growing total debt (private and public) significantly faster than GDP.

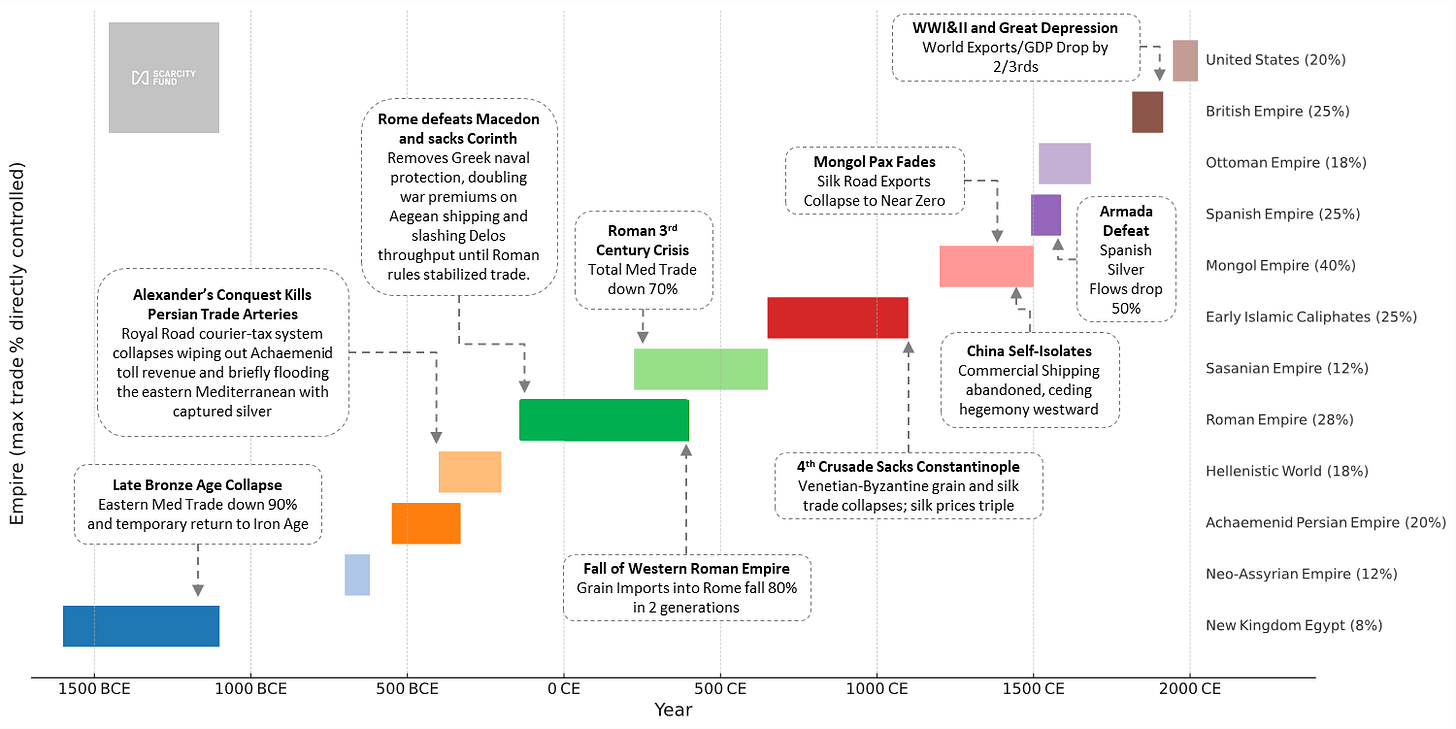

Global Trade Hegemons and their Currency Systems Collapse Every 250-500 Years:

History is unforgiving: trade hegemons and their monetary orders don’t last. About every 250–500 years, the promises of the dominant power outrun its productive base. The Dutch guilder, the British pound, and now the U.S. dollar trace the same arc: innovation, ascendancy, overreach, then debasement. A hegemon must excel at five core disciplines, and the U.S. is slipping versus China in all five. Note that what follows is not an argument for China’s current system. We’re arguing for a restoration of the Western playbook that prevailed 80 years ago: fiscal sobriety and real productivity over financial engineering.

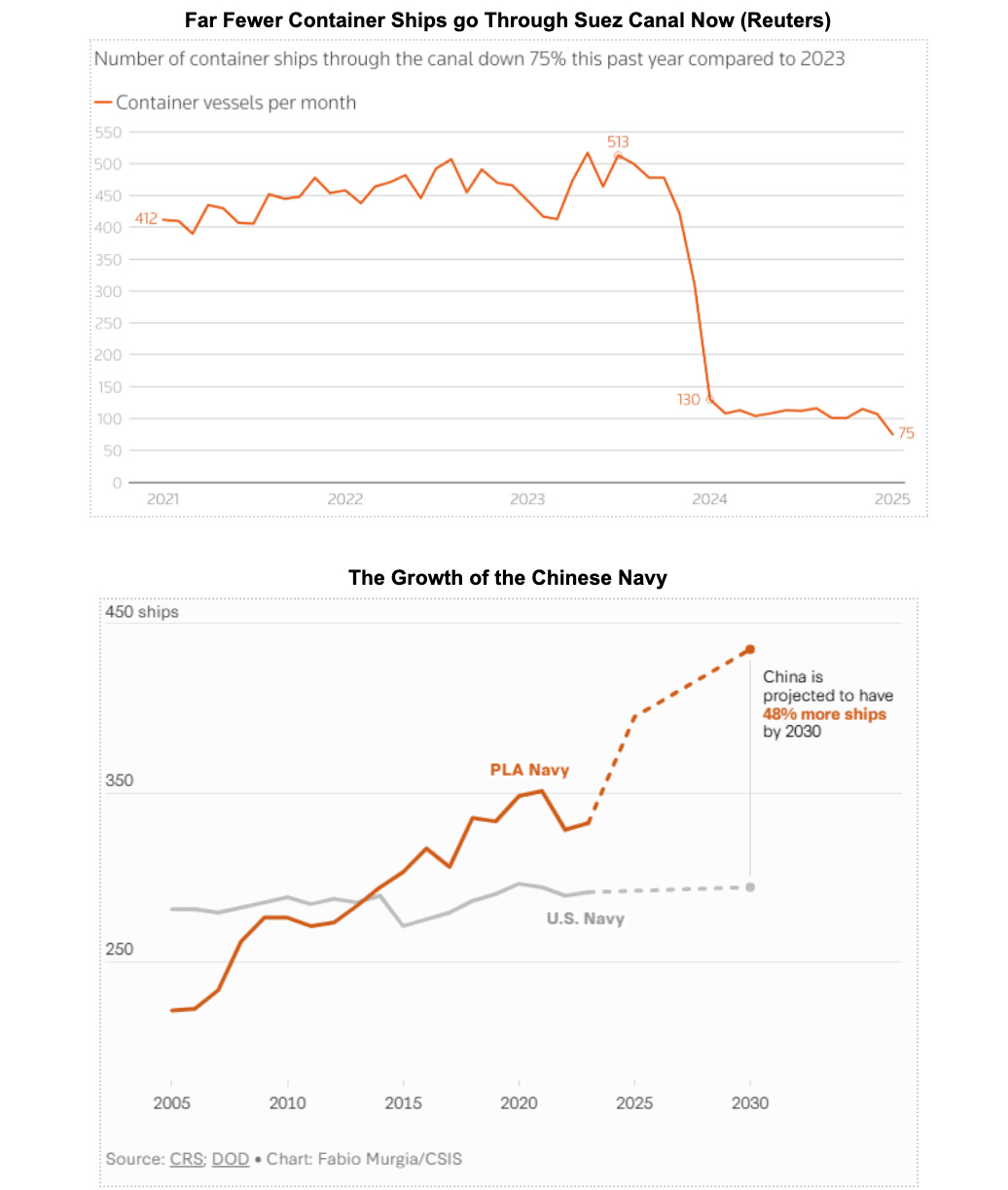

Military Escalation Dominance and Control of Trade Lanes45

A hegemon must project force and secure global commerce. Yet the U.S. has been unable to subdue Russia in Ukraine or even the Houthis in Yemen, one of the world’s poorest nations, despite their attacks on global shipping. Nearly all American weapons systems rely on Chinese components or materials, underscoring a hollowed-out defense-industrial base. Russia produces multiples of the armaments of all of NATO combined.46

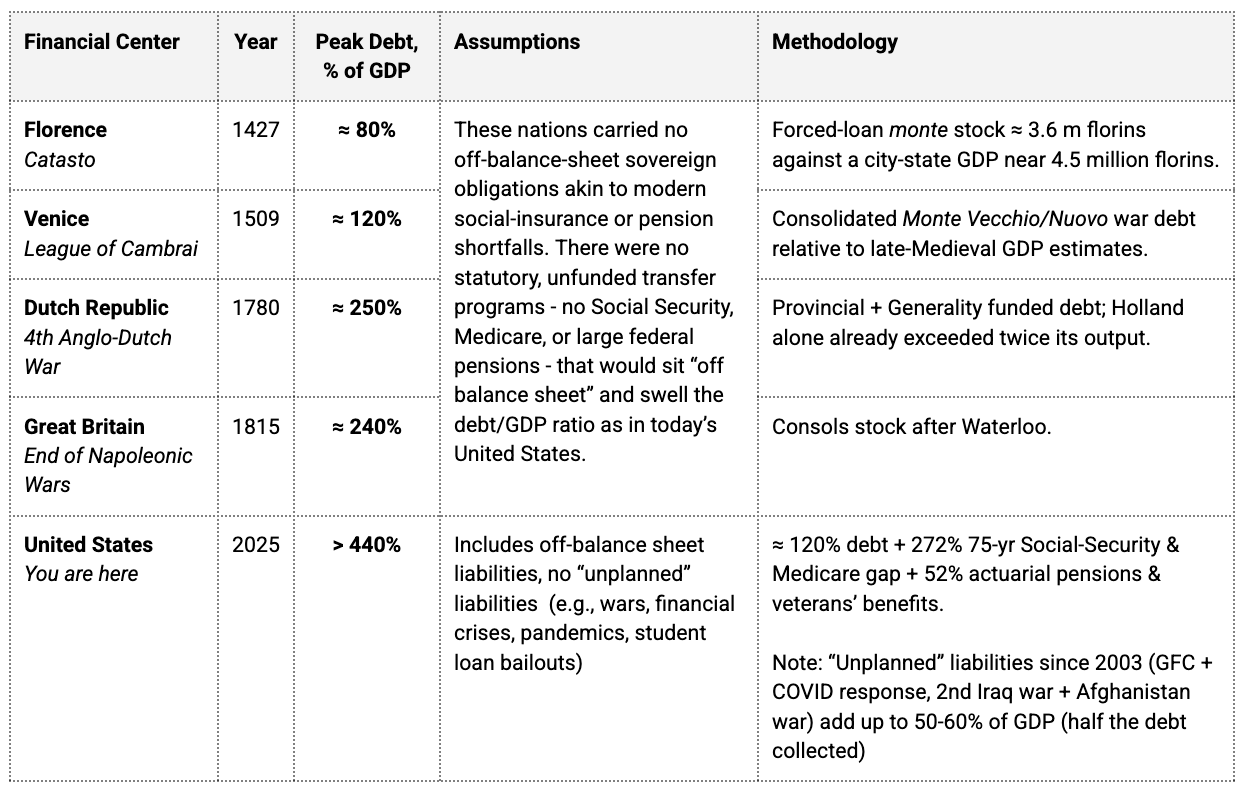

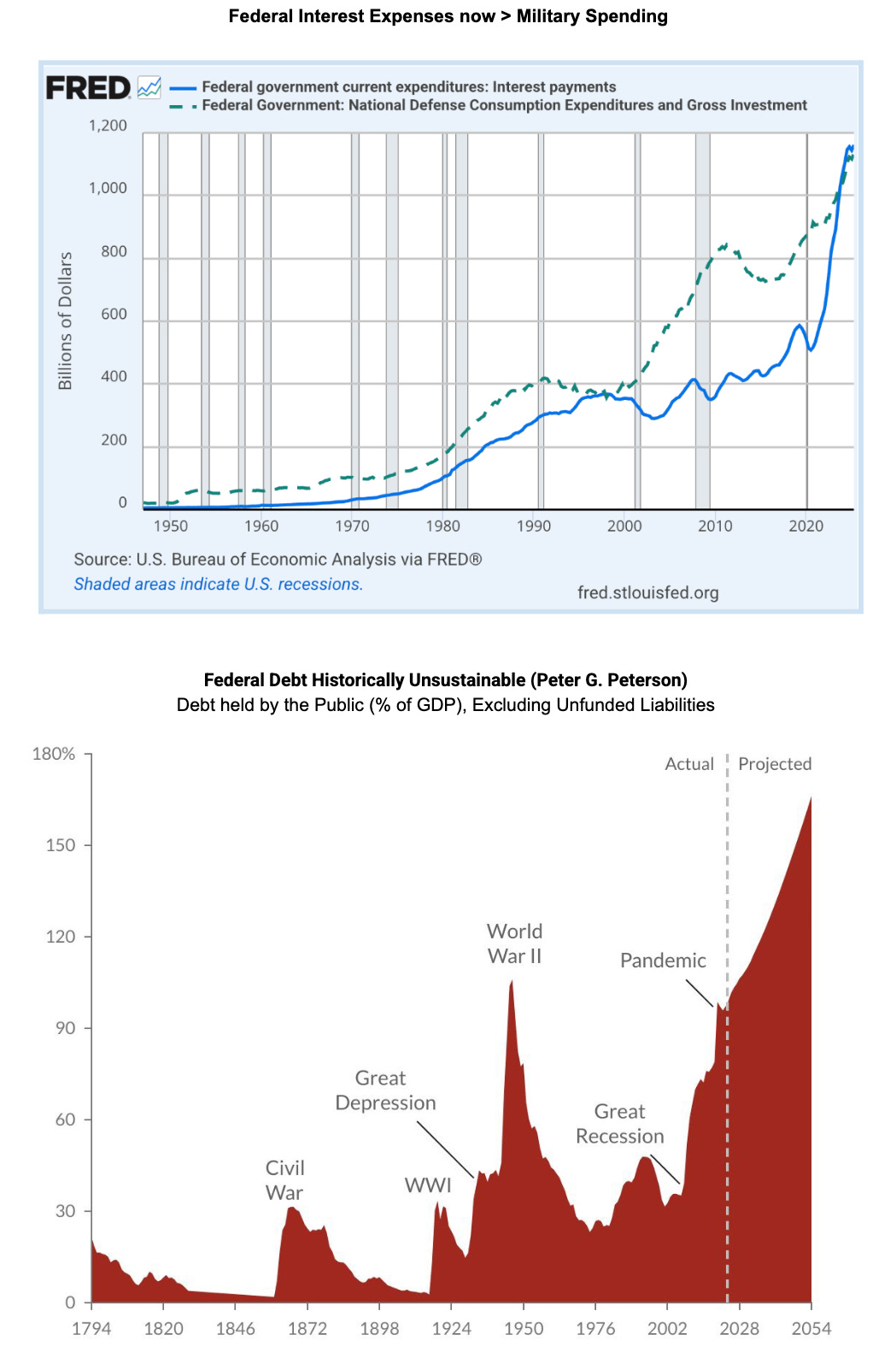

Monetary and Balance Sheet Strength47

Reserve-currency status depends on credibility and discipline. U.S. debt, including unfunded entitlements, now exceeds 400% of GDP, nearly double the burden of any prior financial hegemon48. Interest expense on federal debt has surpassed military spending, while gold trades above $4,000 per ounce, signaling growing doubt in the dollar’s real value.

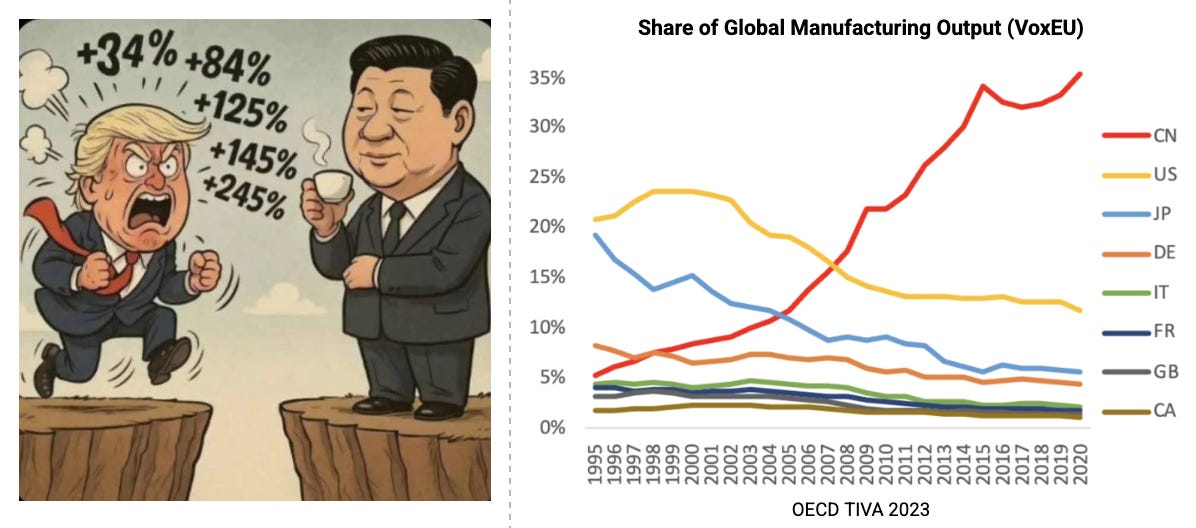

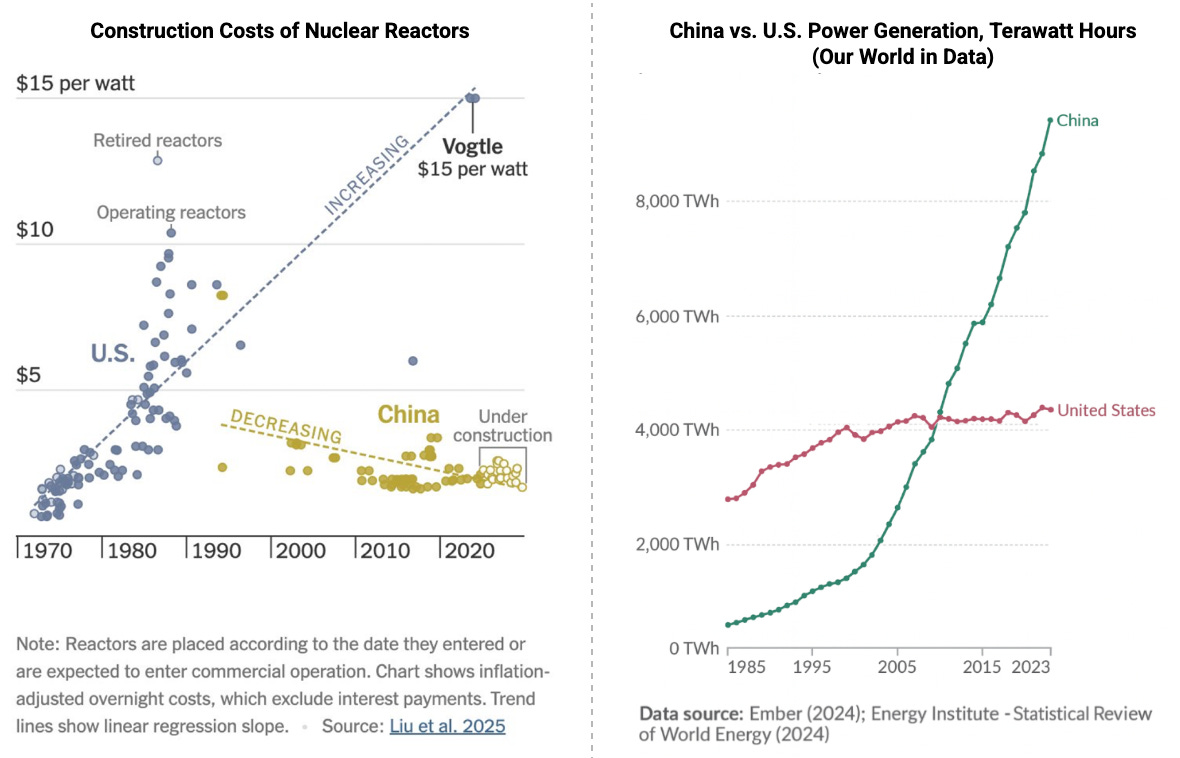

Manufacturing and Productive Capacity

Real goods ultimately anchor financial power. That anchor has slipped. China now produces 35% of global manufacturing output49, roughly double the U.S. share, and generates approaching three times as much electricity50. America’s industrial base has withered into dependence on global supply chains it no longer controls.

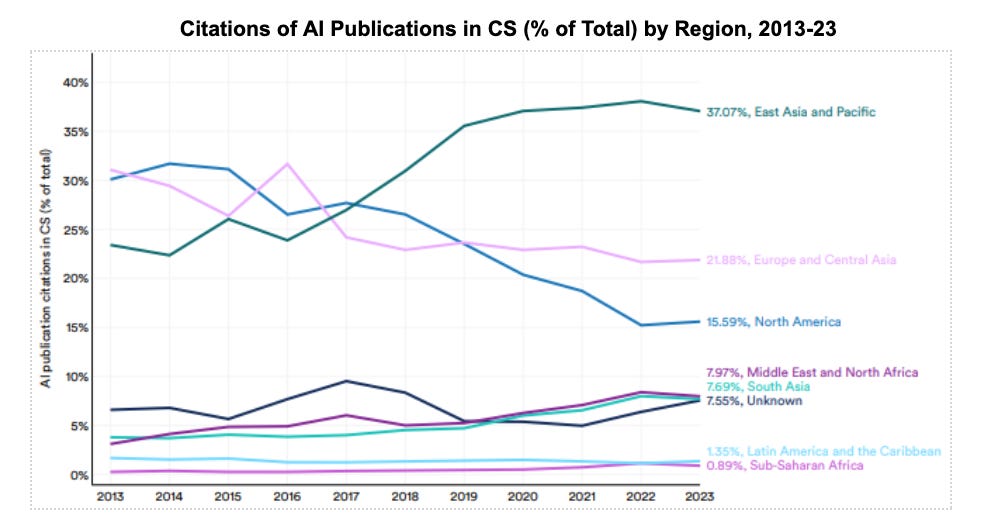

Technological Innovation51

Innovation is indispensable, but it compounds only when done the right way: anchored in domestic production, measurable productivity gains, sound economics, and patient accountable capital. In the U.S., over-financialization and cozy public-private arrangements have crowded out real invention, inflating the near-term commercial promise of technologies like nuclear fusion, carbon capture, quantum computing, LLM-based AGI, and blockchain smart contracts. Even in artificial intelligence, open-source Chinese models now rival Western counterparts, hinting that the next technological cycle may no longer be U.S.-led.

Cultural and Institutional Cohesion (the most important)52

Sustained power requires unity, trust, and a coherent social narrative. The U.S. today is paralyzed between extractive, oligarchical factions on both the left and the right, unable to make long-term strategic decisions or mobilize collective purpose. Public trust in government and mass media is at all-time lows and political polarization is reaching dangerous extremes. In this context, counterparties price in U.S. incoherence. Why would Beijing strike a grand bargain with a president who may soon be a lame duck? Hence the narrow trade truce: a one-year rare-earths reprieve designed to lapse after the U.S. midterms, teeing up a renegotiation.

Nuclear Power as a Case Study in Hegemony53:

Becoming the world leader in nuclear power demands hegemonic capabilities: abundant capital, long-term planning at the societal level, the stockpiling and refinement of sufficient fuel, fast but sensible permitting, fuel-cycle mastery, heavy-industry depth, massive grid build-out, and frontier innovation in reactor design, engineering, and nuclear science. In the 1950-70s, this was the U.S. but today it is becoming China. The United States has begun a course correction (credit to the Trump administration for reopening the door) but regulatory reform is only the first inch of a marathon. The real tests are institutional staying power and the speed of rebuilding the knowledge base, supplier networks, productive scale, long-horizon fuel security, and an R&D engine (from advanced materials and fuel-cycle chemistry to safety modeling) after decades of neglect.

China is not standing still. On Nov 1, 2025, China’s SINAP achieved the first in-reactor thorium to U-233 conversion in a thorium-loaded molten-salt reactor and is targeting a 100-MW demo by 2035, putting China in front in the advanced-nuclear race.54 Thorium MSRs promise superior economics and resilience because thorium is 3x more abundant and the cycle can avoid enrichment, a step that makes up nearly half of nuclear fuel cost.55 The U.S. pioneered MSRs in the 1960s (ORNL’s MSRE ran 1965–69 and first used U-233 in 1968) but then abandoned the research, now ceding the lead to China.56

4. AGI is Optional: Diffusion Becomes the Business Model

Ironically, a steep market value correction and new discipline around capex efficiency may be exactly what U.S. hyperscalers need to become… more Chinese. In China, the focus is not on building ever-bigger models, but on making AI useful. The priority is practicality: adding capacity cheaply, lowering energy demands, tightening feedback loops, and embedding AI into robotics, logistics, and manufacturing. The standout example is DeepSeek, the Chinese model that achieved GPT-4-level reasoning on a fraction of the compute. Its architecture emphasizes efficiency over brute force with fewer parameters, smarter routing, and better integration with edge hardware. It signals a turning point: intelligence per watt, not per dollar of GPU. By contrast, American firms still chase scale for its own sake and lazily try to create singular frontier models that solve all problems through infinite compute. The crash will force the U.S. giants to focus on applied intelligence to generate revenue. It won’t be about AGI, but rather AI as infrastructure, quietly embedded in operating systems, workflows, and supply chains.

But the second turn of irony will come when firms realize that diffusion itself, the messy work of embedding AI into everyday life, is the real path to AGI. By placing models into banal contexts, from customer service to warehouse logistics, we will unlock a vast new reservoir of real-world data, finally extending beyond the internet or books the models have already consumed. At the same time, the length of time agents can focus will expand. Just as Tesla advanced autonomy not by refining simulation labs but by putting millions of cars on real roads, so too will AI systems mature through contact with reality. Commercial pressure will drive architectures that sustain attention over longer horizons, learn from delayed outcomes, and adapt incrementally. In other words, diffusion will generate more data, and innovation will generate more focus. In trying to commercialize AI, we will inadvertently teach it context, decision making, and persistence. The road to AGI will not run through bigger models, but through more exposure: the billions of unscripted interactions that come from turning the idiot savant loose in the physical economy.

Let’s take the example of call center automation today to illustrate what needs to happen. Automating a call center with AI is slow, expensive, and packed with human effort at every step. Before an AI can even handle simple customer questions, teams of people must57:

Manually label data. Thousands of past calls and chat transcripts need to be read and hand-tagged by humans so the model can recognize basic “intents” like “refund,” “shipping delay,” or “cancel order.”

Train narrow bots. Engineers then fine-tune small task-specific models for each flow (returns, password resets, billing disputes). Each one requires its own dataset and tuning.

Wire up fragile tool chains. Developers craft brittle sequences of API calls so the bots can talk to customer systems like CRMs, payment processors, or inventory databases. One software update can break the whole chain.

Add guardrails and test endlessly. Red-teaming and safety reviews take months. Every possible failure, like giving a refund to the wrong person, has to be simulated and patched.

Keep humans in the loop. Because models still hallucinate, miss rare edge cases, and can’t hold long conversations reliably, companies must keep live agents supervising or “catching” the AI’s mistakes.

The end result? After all that effort, the system might deflect a few FAQs or triage simple tickets, but anything complex still escalates to a person. Quality assurance staff stay busy, the old phone menu (“press 1 for billing...”) never goes away, and the ROI barely pencils out.

Now envision an AI product built for diffusion into the call center space - a “call center in a box” which is a zero-touch, cloud service that ingests years of historical calls and tickets, listens, and then auto-builds ~90% of the system:

Self-discovery. Unsupervised clustering over transcripts to map intents, failure states, and actual resolution policies; aligns these with SLAs and business rules learned from logs.

Auto-playbooks. Synthesizes policy-faithful flows (refunds, replacements, cancellations, fraud checks) with executable guardrails. It compiles these into tool-using agents bound to your CRM, billing, KMS, and ID-verification APIs.

Safety & eval harness. Generates adversarial test suites from past escalations and legal/compliance flags; runs continuous offline evals until pass-rates clear thresholds, then ships with built-in monitors for drift and anomaly detection.

Live-ops loop. Every live interaction updates the policy graph, retrains retrieval indices, and tunes handoff thresholds, tightening the loop without a labeling team.

Governance out-of-the-box. Role-based access, audit logs, and reversible actions; any irreversible operation (e.g., wire transfers) requires multi-factor approvals the agent can request/schedule.

Let’s be clear: building a true “call center in a box” would be a monumental undertaking, demanding breakthroughs across AI, data engineering, and human-machine governance. But it’s very likely not AGI. Regardless, once achieved, it becomes an engine that can eat call center work worldwide. It’s not the kind of project you pursue if you believe that infinite compute and ever-larger language models alone will deliver first-mover self-recursing AGI utopia. But when call center automation becomes a push-button exercise, its spread will follow the classic S-curve: slow at first, then straight up. Essentially, it would largely take humans out of the loop of the diffusion itself.

Incidentally, global call center employment remains a massive, steadily expanding segment of the service economy. Industry estimates suggest that as of 2024, call centers employed roughly 3 million people in the United States alone58, while global job creation added about 69,500 new positions across 110 new or expanding facilities that year59. Although precise worldwide headcounts are difficult to obtain, market valuations help illustrate the scale: the global contact-center industry was worth approximately US $352 billion in 2024, with projections reaching nearly US $500 billion by 203060. Taken together, these figures point to an industry employing many millions worldwide, and still expanding despite gradual automation pressures. There is enormous value, and considerable disruptive pain, in the race to build the first true “call center in a box.”

So, the real questions are whether we can reach that point, and, if so, when. We believe that demographic pressures and geopolitical realities will keep pushing us in that direction, even if the outcome may not serve our collective best interest. A “call center in a box” fits neatly into this trajectory: it addresses shrinking workforces in aging economies while reducing reliance on Asian supply chains, an appealing proposition for both policymakers and executives seeking to cut costs, even at the cost of deeper human displacement.

We will discuss this in depth in Chapter II, How to Invest in the Next Decade.

5. Jobs Suddenly Start Disappearing: The Noticing Comes too Late

It is increasingly clear that for bounded, single-player analytical work, we are already edging into the steep part of the S-curve, and it’s quietly devouring entry-level knowledge jobs. The pattern is nearly identical across industries: a solo contributor sits at a laptop, queries structured data, applies a playbook, and delivers a report, memo, or model. That workflow (repeatable, evaluable, and grounded in past data) is exactly where small models paired with retrieval and automation tools now outperform human hours on cost, speed, and consistency.

You can already see the erosion in practice. Mid-size law firms are cutting document-review teams by >75% after adopting legal-AI assistants.61 Tax prep chains now use LLMs to auto-populate returns and cross-check deductions before a CPA ever opens the file. Strategy consulting firm analysts privately admit that first-draft slides are now generated by in-house GPT pipelines trained on past decks - their real work begins at version three. Even bulge-bracket investment banks quietly use internal copilots to parse 10-Ks, build valuation comps, and summarize earnings transcripts, tasks that once consumed armies of first-year analysts. JP Morgan is publicly considering moving from 6 junior analysts per one team lead to 4-to-1 instead.62 This shift spans support roles like paralegals and audit associates to prestige ones like coders, researchers, and junior consultants/i-bankers. The loss isn’t just economic, it erodes the apprenticeship ladder that once taught craft through repetition. Where young professionals once learned judgment by producing and re-producing drafts, they now review machine outputs. This reality is probably starting to show up in macroeconomic data as well, yet is barely being noticed (see charts below)63.

So we are left with a set of uncomfortable questions:

How steep is the S-curve for bounded, single-player analytical work? Will GPT-7 replace business analysts, accountants, and other white-collar apprentices entirely? If so, when?

Can the harder problem of non-bounded diffusion, the embedding of AI into messy, multi-agent real-world contexts, be solved? And if it can, how long will it take?

Finally, if diffusion succeeds, will this transition resemble prior industrial revolutions, in which displaced workers eventually migrated to “higher-value” tasks?

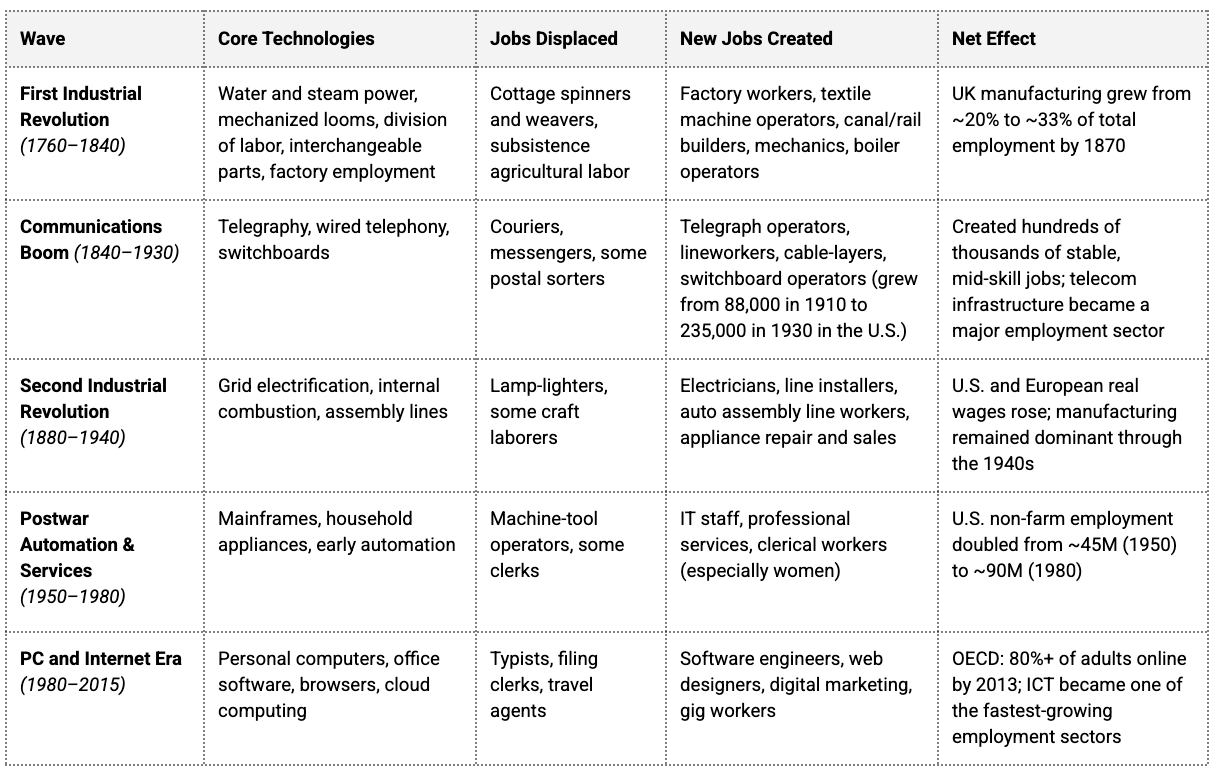

Answering these questions in full is still not possible. However, what we believe we do know (and can show) is that if the diffusion problem is solvable, this won’t be anything like past industrial revolutions. What makes this revolution different is that it ultimately replaces rather than augments human synthesis, planning, agency, and perhaps even creativity. In prior eras, foundational technologies extended human capability64:

Steam power expanded the physical reach of artisans and engineers.

Electrification created entirely new cognitive professions - chemists, managers, patent lawyers.

Microprocessors made abstract logic the economy’s most valuable input, fueling decades of wage growth for the educated.

Each wave displaced muscle or rote computation, freeing humans for judgment, imagination, and coordination. But this time is different, as it hits cognitive jobs at the top of the labor stack. If pushed far enough, the link between human productivity and household income will, at least temporarily, break. Given how ominous this is, we decided to model the predicament we’d be in if diffusion were to be solved in the nearterm (next 5-10 years).

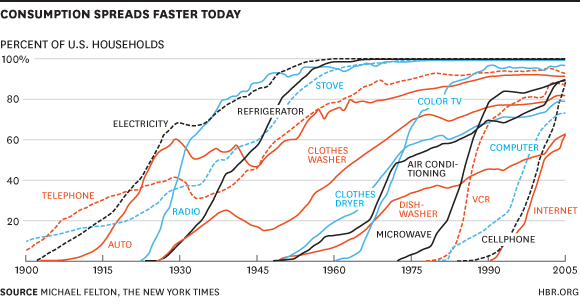

Let’s start by building some intuition around S-curves. As the chart below65 shows, adoption begins slowly, then suddenly explodes. And over time, technology S-curves have been getting steeper, meaning new innovations spread faster than ever before.

Similarly, on a logarithmic scale, computations per dollar has traced a near-straight line for roughly 85 years66. That apparent continuity isn’t one long S-curve but a series of successive S-curves: electromechanical relays → vacuum tubes → discrete transistors → integrated circuits → GPUs → modern AI accelerators. Each paradigm nears a plateau, then the next rises, so the aggregate price-performance S-Curve hasn’t shown a flattening yet. Conceptually, this arc even reaches back through Babbage’s mechanical engine to earlier calculating devices like the abacus.

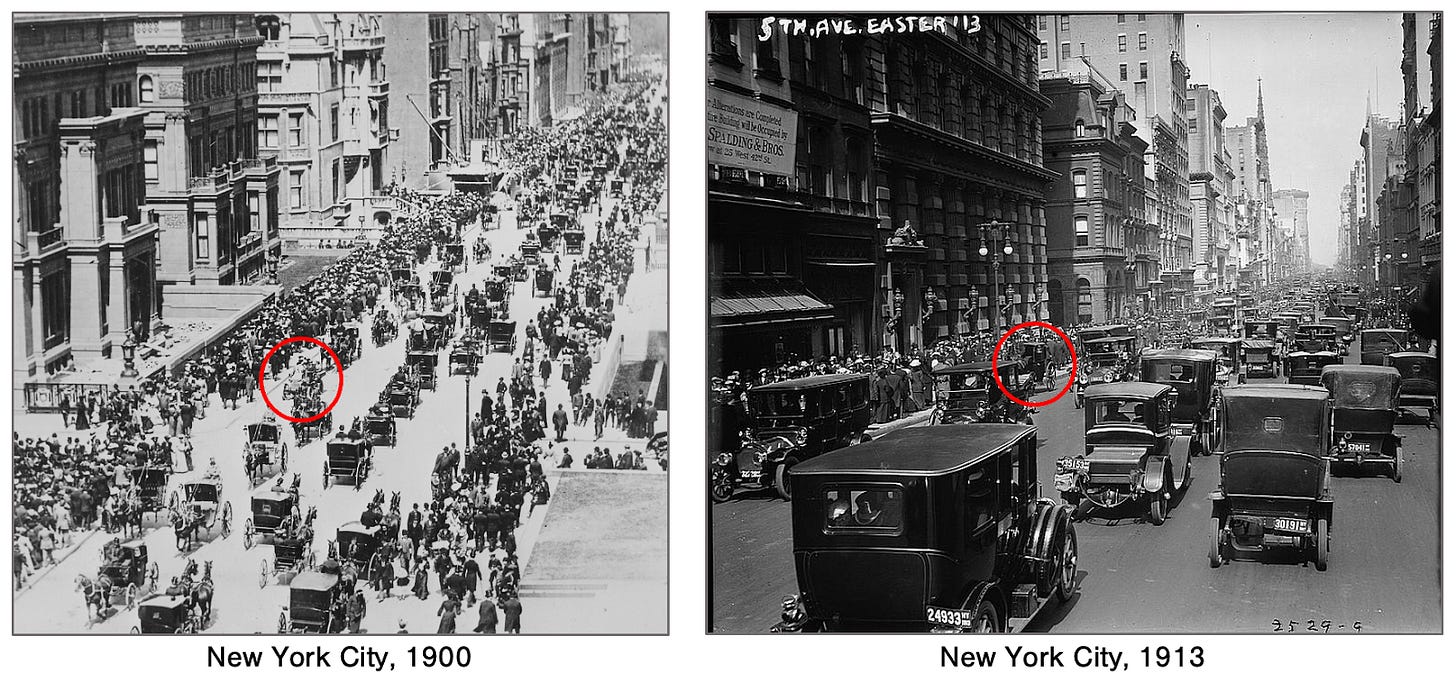

You cannot internalize this without real-world examples. Consider the two famous turn-of-the-century NYC photos below67. In 1900, a New York City street is packed with horse-drawn carriages, with a single automobile barely visible. Thirteen years later, the same street shows the reverse: one lonely carriage surrounded by a sea of cars.

Now imagine what those thirteen years actually meant. Cities had to dispose of hundreds of thousands of horses which once produced so much manure that sanitation was a daily crisis. Entire industries (blacksmithing, stable management, saddle-making, feed supply chains) collapsed. Streets were torn up to lay asphalt and fuel stations, while factories for engines, tires, and steel rose in their place. The shift even changed what cities smelled like, from hay and waste to oil and exhaust. When diffusion takes off like that, it’s already too late to steer it. The transformation feels sudden only in hindsight. By the time the S-curve bends upward, it’s already rewriting everything beneath it.

An Oldsmobile advertisement from 1903 feels oddly appropriate today.68

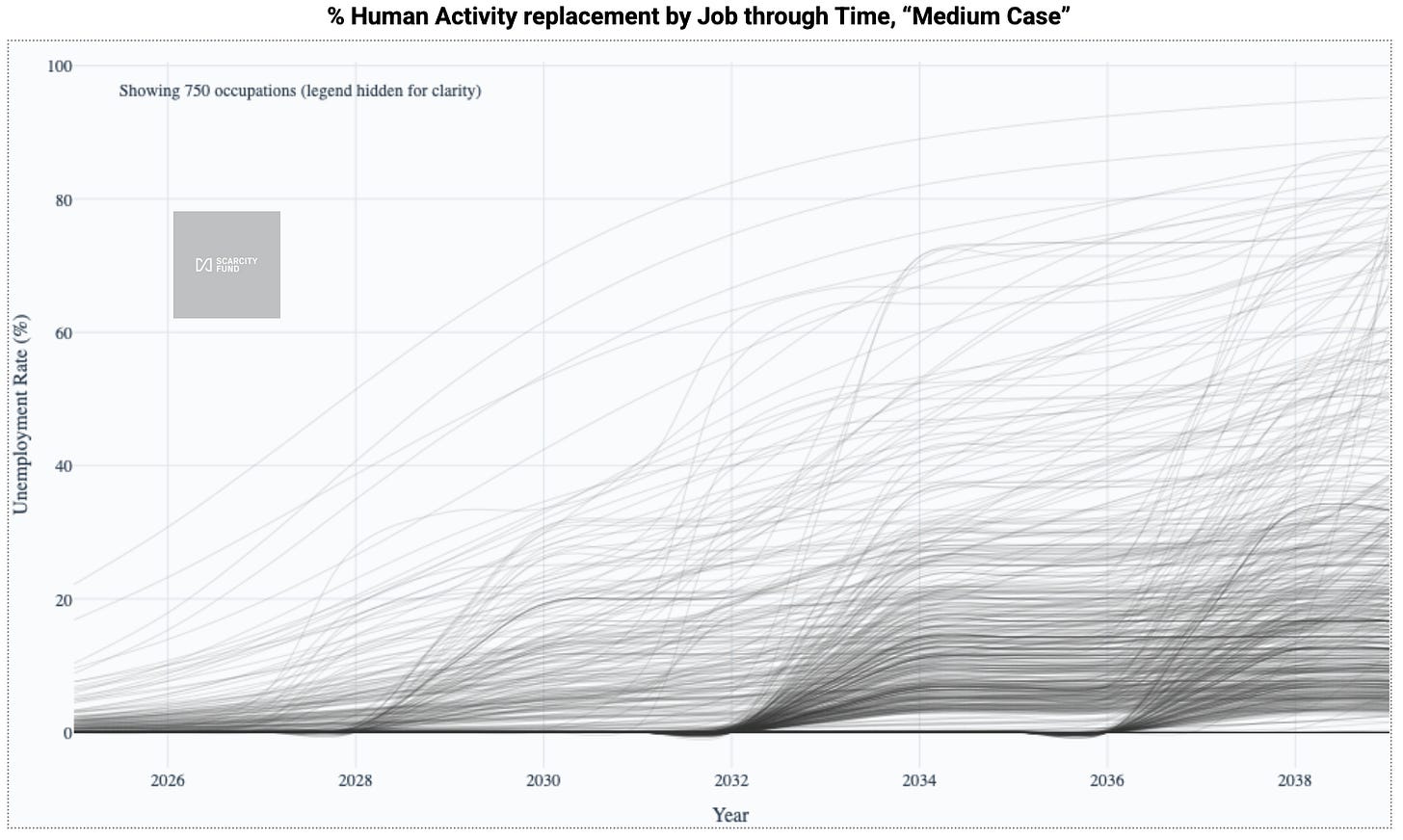

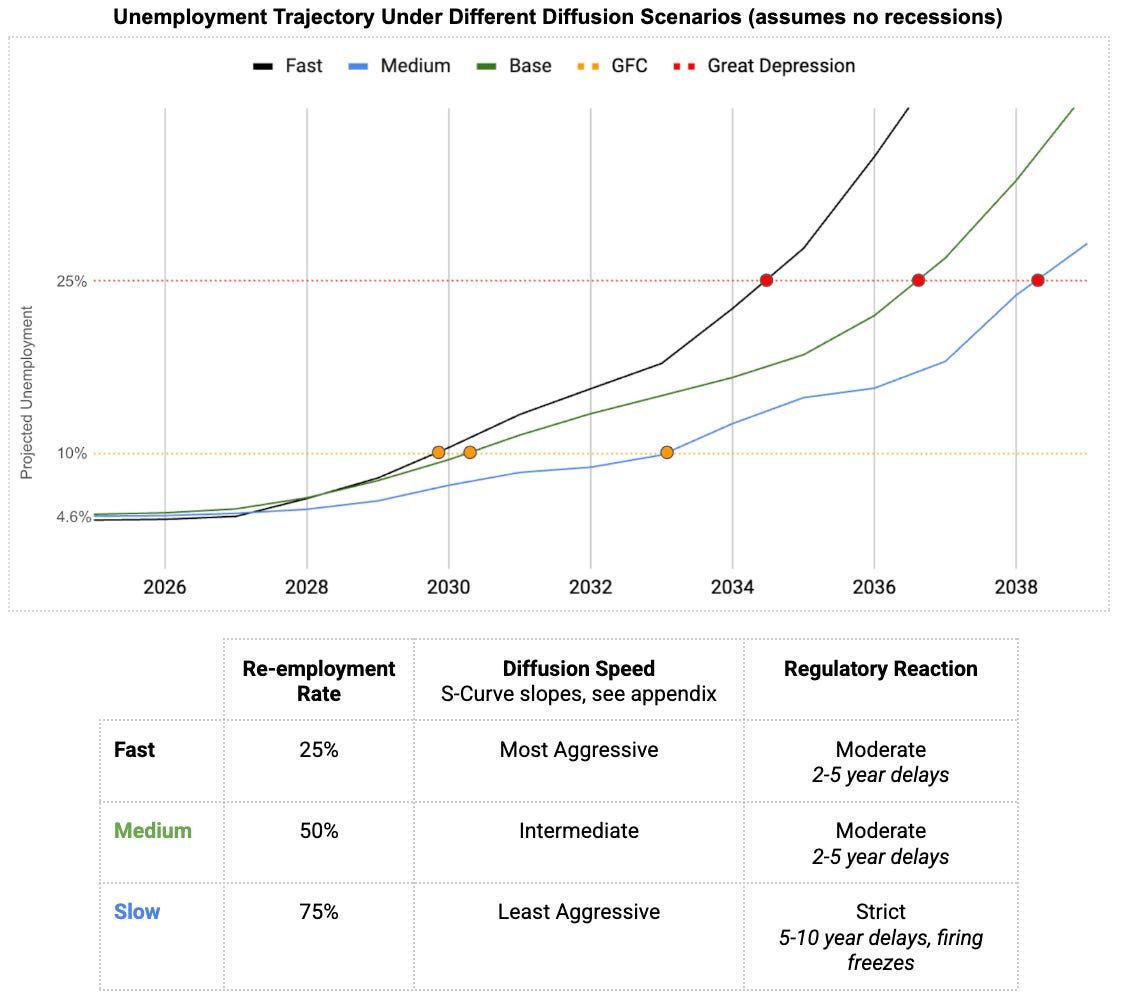

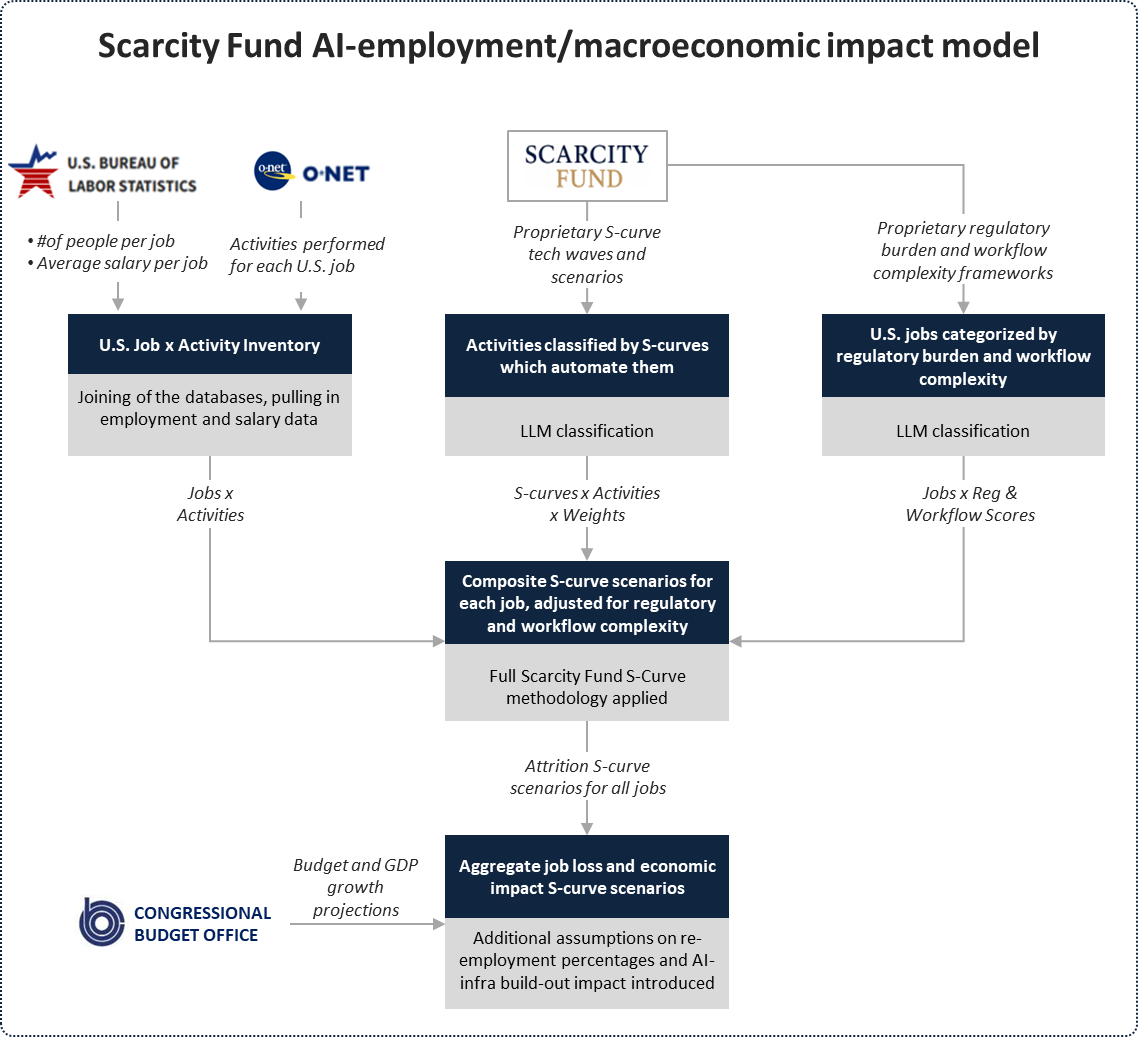

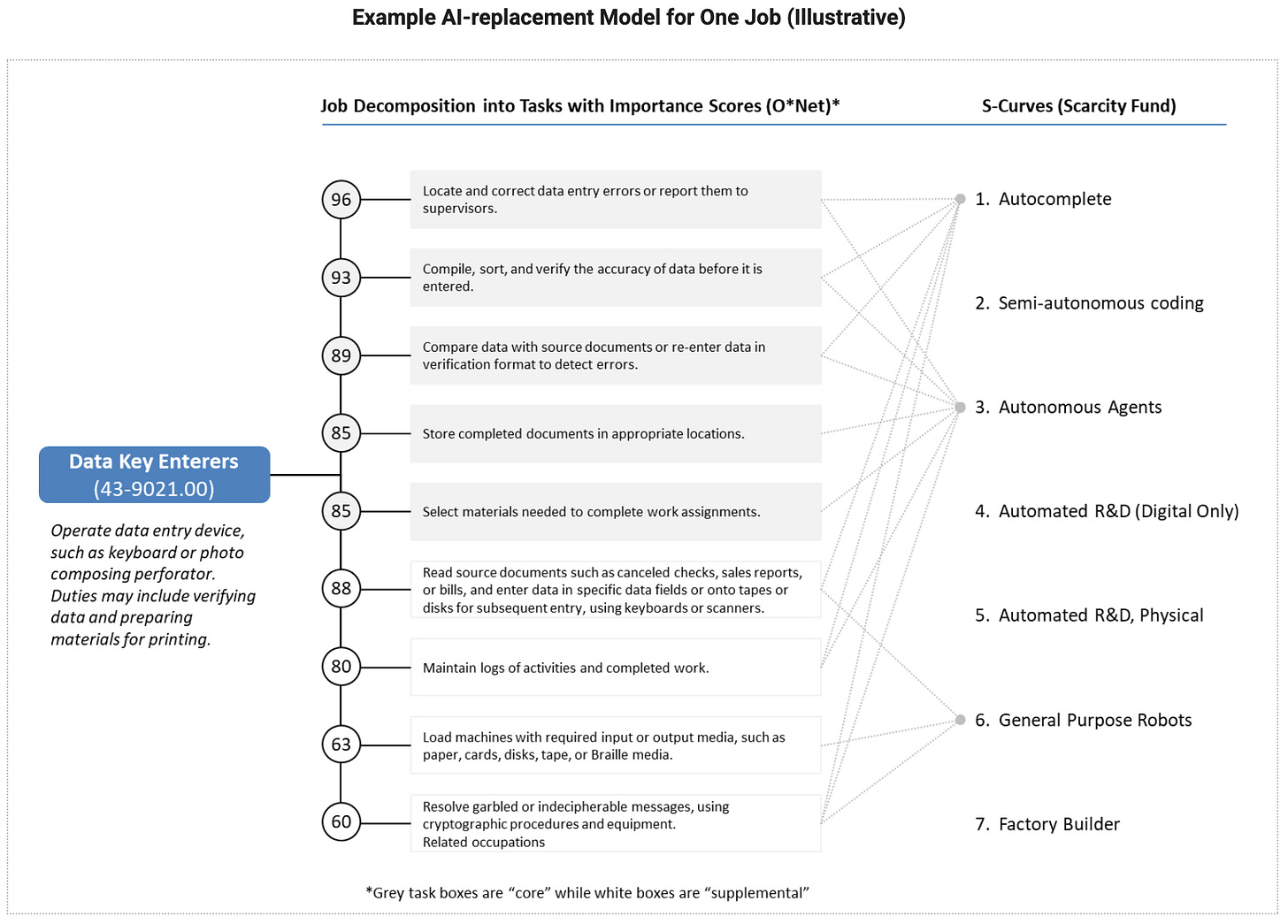

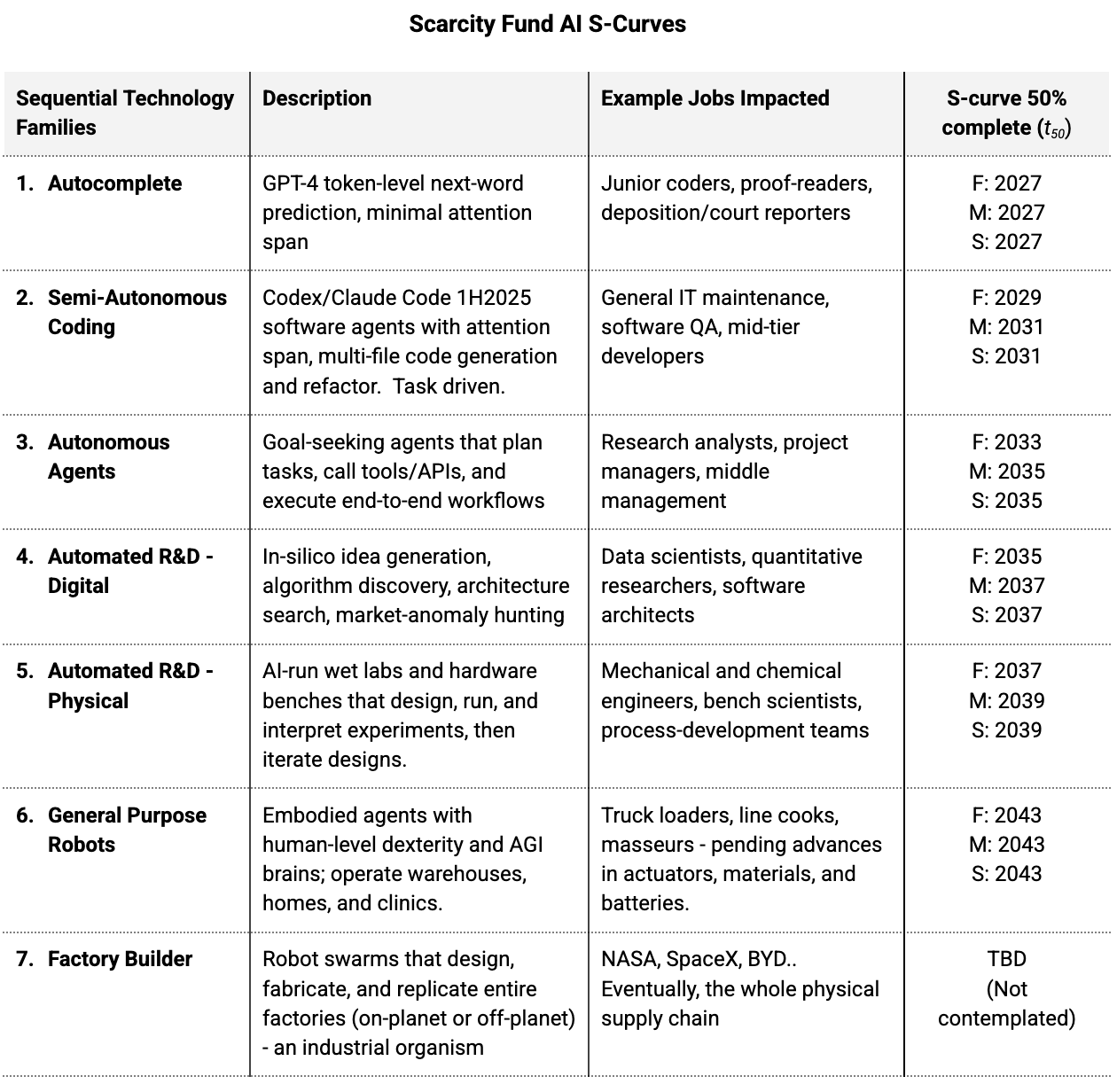

So it shouldn’t come as a surprise when we say that IF AI diffusion starts being solved, it will be a major economic shock. Our analysis takes a bottoms-up approach using government data: we classify roughly 20,000 distinct tasks across 1,000 occupations in the U.S. by how susceptible each is to successive stages of AI capability. We then model adoption as a series of AI S-curves, each with its own midpoint and steepness, weighted by the share of tasks it can automate within each job category. These diffusion curves are linked to employment and wage data to estimate their aggregate economic impact. The detailed methodology is in the appendix. The resulting diffusion trajectories for our “medium scenario” by jobs are shown below to illustrate the bottoms-up outputs of our model.

If this AI economic diffusion were to take off, it would have a dramatic, and, we believe, mostly irreversible impact on employment69:

For perspective, U.S. unemployment peaked around 10% in the GFC, ~15% (briefly) during COVID, and ~25% in the Great Depression. Unlike the 1930s, this downturn would be structural, not cyclical, permanent displacement rather than a temporary layoff-and-rehire cycle, and it will unfold in waves: first symbolic-analytic white-collar work (proofreaders, paralegals, junior engineers), then the service backbone (HR, admin assistants, appraisers), front-line services (stockers, food prep, light-truck drivers), and eventually the more skilled physical trades if robotics innovations continue on current pace. New jobs will emerge, but this revolution is substitution-heavy and the velocity of replacement will outpace retraining and job creation, making timely re-employment, and fiscal stability, unlikely.

Notably, even with rapid re-employment (the slow case assumes 75% within a year of being laid off), the parabolic phase of the S-Curve runs so fast that labor markets simply cannot keep up. A world in which AI diffusion takes off broadly (and soon) would look something like this:

Investor Note

Our goal is to understand the future so we can face it with clarity rather than surprise. The key takeaway is simple but sobering: the road ahead will be volatile and perilous. The only real defenses are having the right frameworks, attentive observation, and the discipline to stay flexible and active. In each of these cases, finding what’s scarce will be the path. Right now, compute (and its value chain) is scarce (albeit for bad reasons). In a monetary debasement, hard money is scarce.

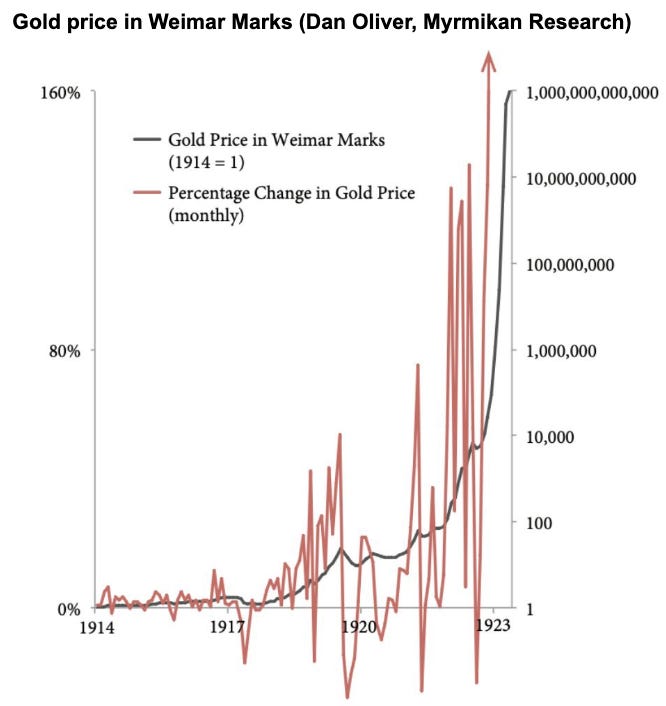

Even with this knowledge, humility is a must. One of our favorite reminders of this comes from history: the price of gold in Weimar marks during Germany’s hyperinflation. It shows that you can be absolutely right about the direction of events, and still lose everything if you’re levered70.

Next chapter, we’ll dive deeper into our investment approach. As a reminder…

Inflation first, deflation later. The monetary singularity will arrive before the technological one and AI is already consuming resources faster than productivity can catch up.

Frontier models ≠ frontier profits. The real money lies in economic diffusion, not in the biggest model.

A 2x levered S&P strategy won’t work in the coming cycle. The winners of the 2030s won’t be the same as the winners of the 2020s.

Methodology: Scarcity Fund Employment Model

Drawing inspiration from the GPTs are GPTs paper71, we combined our estimates of the evolution of AI with granular jobs data to estimate the job-specific S-curves across roughly 1000 jobs. We then aggregate these jobs by total employed and incorporate a simple re-employment model to humble this aggregate.

Legal Disclaimer

Last updated: November 5, 2025

Scarcity Fund is currently an anonymous, independent publisher of free educational commentary on economic, financial, and geopolitical topics. We discuss frameworks, markets, and portfolio constructions to help readers think - not to recommend any action. Nothing here is investment, legal, or tax advice, and nothing is an offer or solicitation. We may hold positions in the instruments we discuss.

1) Educational & Informational Only

All Scarcity Fund publications (including articles, podcasts, emails, posts, and any downloadable materials) are provided solely for educational and informational purposes. They are general in nature and are not tailored to the circumstances or risk profile of any individual or entity.

2) Not Investment, Legal, or Tax Advice

Nothing herein constitutes investment, financial, legal, accounting, or tax advice, or a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any security, commodity, derivative, or strategy. You are solely responsible for your own investment decisions. Consider seeking advice from a qualified professional who understands your objectives, financial situation, and risk tolerance.

3) No Offer or Solicitation

Content is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security or other financial instrument, or to participate in any investment strategy, vehicle, or trading program. If Scarcity Fund or any related entity offers an investment in the future, it will be made only by means of formal offering documents (e.g., a private placement memorandum) and only to eligible investors, after you have had the opportunity to review such documents in full.

4) No Investment Adviser/Client Relationship

Scarcity Fund is not acting as your investment adviser or fiduciary. Accessing or using our content does not create an adviser-client, fiduciary, or other professional relationship between you and Scarcity Fund or any contributor.

5) Forward-Looking Statements & Uncertainty

Analyses may include forward-looking statements, opinions, estimates, scenarios, or projections which involve significant assumptions and uncertainties. Actual outcomes may differ materially. Scarcity Fund has no obligation to update or revise any content.

6) Sources; Accuracy; No Warranties

Information is derived from sources believed to be reliable, including public filings and third-party data providers, but is not guaranteed as complete or accurate. Content is provided “as is,” without warranties of any kind, express or implied, including warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, non-infringement, accuracy, or timeliness.

7) Performance & Risk

Past performance is not indicative of future results. Investing involves risk, including the possible loss of principal. Where hypothetical or backtested performance is discussed, such results have inherent limitations, may not reflect real trading, and are not guarantees of future performance. Trading futures, options, and other derivatives involves substantial risk and is not suitable for all investors. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results. Hypothetical performance is subject to model risk and does not account for all market factors, liquidity constraints, slippage, or fees.

8) Conflicts of Interest; Positions & Trading

Scarcity Fund, its contributors, and related persons may hold, buy, or sell positions in instruments or issuers mentioned, and may trade at any time without notice. We do not undertake to disclose updates to positions. Any views expressed are subject to change without notice.

9) Research Characterization

Content is the publisher’s opinion and does not constitute “independent investment research” as defined by any regulator. It has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of publication.

10) Third-Party Links & References

Links to third-party sites are provided for convenience and do not imply endorsement. Scarcity Fund is not responsible for third-party content, accuracy, or security.

11) Technology, AI, and Data Tools

We may use automated tools (including large language models and other AI systems) in drafting or verifying content. These tools can produce errors or omissions. Human review is applied, but no guarantee of accuracy is made.

12) Jurisdiction; Distribution Restrictions

Content may not be appropriate or lawful for use in certain jurisdictions or by certain categories of investors. Persons accessing our content do so on their own initiative and are responsible for compliance with local laws and regulations.

For UK: Not directed at, or intended for distribution to, “retail clients” as defined by the FCA. For EU: This material is marketing communication and does not constitute an investment recommendation as defined under the Market Abuse Regulation or MiFID II.

13) Limitation of Liability

To the maximum extent permitted by law, Scarcity Fund and its contributors shall not be liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, consequential, special, exemplary, or punitive damages (including lost profits) arising from or relating to your access to or use of the content, even if advised of the possibility of such damages.

14) No Duty to Update; Removals

We may add, modify, or remove content at any time without notice and assume no duty to update any material.

15) Intellectual Property & Limited License

All content is the property of Scarcity Fund or its licensors and is protected by intellectual-property laws. You are granted a limited, revocable, non-transferable license to access and use the content for personal, non-commercial purposes. Any reproduction, distribution, or derivative use requires prior written permission, unless otherwise stated.

16) Privacy

If you submit contact information to receive publications, we will use it to deliver content and manage your subscription. See our Privacy Notice for details.

17) Contact

Questions about this disclaimer may be sent to: contact@scarcityfund.com.

18) Acceptance

By accessing or using Scarcity Fund content, you acknowledge that you have read, understood, and agree to this Disclaimer.

References

Amazon Web Services, “Driving Patient-Centric Innovation in Life Sciences Using Generative AI with Pfizer,” AWS Solutions - Case Studies, 2024, https://aws.amazon.com/solutions/case-studies/pfizer-PACT-case-study/, accessed November 7, 2025. aws.amazon.com

Challenger, Gray & Christmas, Inc., “Pharma and Finance Lead as August 2025 Job Cuts Rise 39% to 85,979,” September 4, 2025, https://www.challengergray.com/blog/pharma-and-finance-lead-as-august-2025-job-cuts-rise-39-to-85979/

Aditya Challapally, Chris Pease, Ramesh Raskar, and Pradyumna Chari, The GenAI Divide: State of AI in Business 2025 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Media Lab, Project NANDA, July 2025), Executive Summary, p. 2. Accessed Nov. 3, 2025. https://mlq.ai/media/quarterly_decks/v0.1_State_of_AI_in_Business_2025_Report.pdf

Gartner, Inc., “Gartner Predicts 30% of Generative AI Projects Will Be Abandoned After Proof of Concept By End of 2025,” July 29, 2024 (Sydney). Accessed Nov. 3, 2025. https://www.gartner.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2024-07-29-gartner-predicts-30-percent-of-generative-ai-projects-will-be-abandoned-after-proof-of-concept-by-end-of-2025

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework: Generative Artificial Intelligence Profile (NIST AI 600-1) (Gaithersburg, MD: NIST, July 26, 2024), PDF, https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ai/NIST.AI.600-1.pdf

K. Owens et al., “Managing a ‘responsibility vacuum’ in AI monitoring and governance in healthcare: a qualitative study,” BMC Health Services Research (2025), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/41023723/

Links to examples of AI excellence on complex bounded tasks:

OpenAI, GDPval: Evaluating AI Model Performance on Real-World Economically Valuable Tasks, PDF white paper (San Francisco: OpenAI, 2025), sec. 5 “Limitations” (“Focus on self-contained knowledge work”; “Tasks are precisely-specified and one-shot, not interactive”), accessed November 1, 2025, https://openai.com/index/gdpval/ (PDF: https://cdn.openai.com/pdf/d5eb7428-c4e9-4a33-bd86-86dd4bcf12ce/GDPval.pdf)

Torsten Sløk, “AI Adoption Rate Trending Down for Large Companies,” The Daily Spark (Apollo Academy), September 7, 2025, https://www.apolloacademy.com/ai-adoption-rate-trending-down-for-large-companies/

Qishuo Hua, Lyumanshan Ye, Dayuan Fu, Yang Xiao, Xiaojie Cai, Yunze Wu, Jifan Lin, Junfei Wang, and Pengfei Liu, “Context Engineering 2.0: The Context of Context Engineering,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:2510.26493 [cs.AI], posted October 30, 2025, https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.26493

Archana Warrier, Thanh Dat Nguyen, Michelangelo Naim, Moksh Jain, Yichao Liang, Karen Schroeder, Cambridge Yang, Joshua B. Tenenbaum, Sebastian Vollmer, Kevin Ellis, and Zenna Tavares, “Benchmarking World-Model Learning,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:2510.19788 [cs.AI], posted October 23, 2025, https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.19788

Nick Lichtenberg, “Without Data Centers, GDP Growth Was 0.1% in the First Half of 2025, Harvard Economist Says,” Fortune, October 7, 2025, https://fortune.com/2025/10/07/data-centers-gdp-growth-zero-first-half-2025-jason-furman-harvard-economist/, accessed November 1, 2025

Trân Nguyễn, “Power Bills in California Have Jumped Nearly 50% in Four Years. Democrats Think They Have Solutions,” AP News, June 6, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/california-high-power-bills-solutions-pge-5cd701688b601ef09b63adbc39af844b, accessed November 1, 2025.

A tail of two AI booms charts:

Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research, AI: In a Bubble (Oct 22, 2025) — chart built from U.S. BEA investment data (NIPA/Fixed Assets)

Efrati, Amir. “‘AI Native’ Startups Pass $15 Billion in Annualized Revenue.” The Information. June 10, 2025. Accessed November 1, 2025. https://www.theinformation.com/articles/ai-native-startups-pass-15-billion-annualized-revenue

Evan (@stockmktnewz) on X; underlying data from company filings (Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet, Meta; 2018–2025; includes finance leases)

GW&K Investment Management, Global Perspectives (October 2025), Figure 2, “Average Capital Expenditures to Sales for Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, and Microsoft.” Sources: GW&K Investment Management, Bloomberg, and Macrobond. Accessed November 1, 2025. https://www.gwkinvest.com/wp-content/uploads/GWK-Global-Perspectives-October-2025-1.pdf

Alphabet Inc., Form 10-K for the fiscal year ended Dec. 31, 2024, U.S. SEC EDGAR

Internal Revenue Service, “Additional First Year Depreciation Deduction (Bonus) - FAQ,” last updated May 29, 2025, https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/additional-first-year-depreciation-deduction-bonus-faq

Matt Rosoff, “Microsoft just revealed that OpenAI lost more than $11.5B last quarter,” The Register, October 29, 2025, accessed November 1, 2025, https://www.theregister.com/2025/10/29/microsoft_earnings_q1_26_openai_loss/

Google Finance, accessed November 14, 2025.

Chart reproduced from BCA Research (2025), using data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts (private fixed investment in information-processing equipment and software and gross domestic product, 1985–2025).

Chart reproduced from GQG Partners LLC, “Tech Part II: CapEx (% of EBITDA),” based on Bloomberg data for S&P 500 companies, 1997–2025 (Amazon, Alphabet, and Meta FY25; Microsoft and Oracle FY26).

Bloomberg News graphic accompanying Emily Forgash and Agnee Ghosh, “OpenAI, Nvidia Fuel $1 Trillion AI Market With Web of Circular Deals,” The Big Take, Oct. 7–8, 2025

Georgia Butler, “Oracle Set to Receive $38bn Debt Package for Data Center Projects—Report,” Data Center Dynamics, October 24, 2025, accessed November 1, 2025, https://www.datacenterdynamics.com/en/news/oracle-set-to-receive-38bn-debt-package-for-data-center-projects-report/

Alphabet Inc., Form 10-Q for Q3 2025 and press materials (cash & securities $98.5B; total debt ≈$26.6B); Microsoft Corp., FY26 Q1 Financial Statements (cash & short-term investments $102.0B; total debt $43.2B); Meta Platforms, Q3 2025 Prepared Remarks (cash & marketable securities $44.45B; debt $28.8B). Combined net cash ≈ $146B as of Sept. 30, 2025.

Brian Contreras, “Venture Capital Has Never Been This Obsessed With AI, New Data Shows,” Inc., April 3, 2025, https://www.inc.com/brian-contreras/venture-capital-artificial-intelligence-ai-openai-pitchbook-data/91170714, accessed November 1, 2025

Ananya Gairola, “Nvidia Is Producing ‘Unprecedented Wealth’ for Its Employees, Nearly 80% Are Already Millionaires: Report,” Benzinga, August 4, 2025, https://www.benzinga.com/markets/tech/25/08/46846592/nvidia-is-producing-unprecedented-wealth-for-its-employees-nearly-80-are-already-millionaires-report

Ethan M. Steinberg, Brody Ford, and Brian W. Smith, “Oracle Raises $18 Billion in Second-Biggest Bond Sale This Year,” *Bloomberg*, September 24, 2025, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-09-24/oracle-looks-to-raise-15-billion-from-corporate-bond-sale.

BofA Global Research. “Borrowing to Fund AI Datacenter Spending Exploded in September and So Far in October.” Research note (chart, Exhibit 1). Bank of America Securities, October 2025.

Berber Jin, “OpenAI Isn’t Yet Working Toward an IPO, CFO Says,” *Wall Street Journal*, November 5, 2025, https://www.wsj.com/tech/ai/openai-isnt-yet-working-toward-an-ipo-cfo-says-58037472.

Deepa Seetharaman, Krystal Hu, and Arsheeya Bajwa, “OpenAI Discussed Government Loan Guarantees for Chip Plants, Not Data Centers, Altman Says,” Reuters, November 7, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/openai-does-not-want-government-guarantees-massive-ai-data-center-buildout-ceo-2025-11-06/

Charlie Bilello (@charliebilello), Creative Planning — post on X (Oct 30, 2025) sharing this “Meta’s Reality Labs (Quarterly Net Loss, $Billions)” chart.

Alex Carver, “CoreWeave’s Earnings Beat Shows That the AI Trade Is Far from Over,” MarketWatch, November 10, 2025, https://www.marketwatch.com/story/coreweaves-earnings-beat-shows-that-the-ai-trade-is-far-from-over-51c141b1

Bubble charts:

Authers, “AI Is Probably a Bubble. Does It Really Matter?” Bloomberg Opinion, September 26, 2025

Robert J. Shiller, “US Home Prices 1890–Present (Real, 1890=100)” - underlying dataset for the long‐run, inflation-adjusted Case-Shiller home price index (Irrational Exuberance). Updated monthly. Accessed November 1, 2025.

“How to Pop a Bubble.” Financial Fables (Substack). Accessed November 3, 2025. https://financialfables.substack.com/p/how-to-pop-a-bubble.

Augur Labs (Augur Infinity) LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/augur-labs_after-surpassing-japans-weight-in-acwi-activity-7352722747463983105-0yy3/

Ned Davis Research (NDR), “Market Cap of Energy, Materials, Consumer Staples, Health Care, Financials, Utilities, and Real Estate vs. Mag 7,” chart, data through November 4, 2025, using S&P Dow Jones Indices; copyright 2025 Ned Davis Research, Inc., accessed November 6, 2025.

Katusa Research. “Market Size Comparison.” Katusa Research, accessed November 13, 2025. https://katusaresearch.com/

Inflation resurgence + K-shaped backlash charts:

David Rosenberg / Rosenberg Research, “Total Share of Population in Economic Expansion” (chart derived from the Federal Reserve’s Beige Book). First posted by Rosenberg on X, Oct. 16, 2025; also discussed in his Substack note on Oct. 21, 2025.

Unusual Whales (@unusual_whales), “US stock ownership by income percentile, per Bloomberg,” X (formerly Twitter), n.d., https://x.com/unusual_whales/status/1917191385201119459. Accessed November 5, 2025.

Global Markets Investor (@GlobalMktObserv), “US consumers’ expected change in their financial situation over the next 5 years is at the LOWEST level in history. Meanwhile, the S&P 500 …,” X (formerly Twitter), n.d., https://x.com/GlobalMktObserv/status/1985716164517879840. Accessed November 5, 2025.

Makortoff, Kalyeena. “JP Morgan boss says more ‘cockroaches’ will emerge after private credit sector failures.” The Guardian, October 14, 2025. Website: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2025/oct/14/jp-morgan-jamie-dimon-losses-private-credit-sector

Credit stress charts:

April Rubin, “Americans Are Behind on Car Payments at a Record Level,” Axios, March 7, 2025, https://www.axios.com/2025/03/07/car-loan-payment-delinquencies-record-high

Nick Villa, “The Office Sector’s Double Whammy,” Moody’s CRE, July 8, 2025, https://www.moodyscre.com/insights/cre-trends/the-office-sectors-double-whammy/

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, 2025 Risk Review (Washington, DC: FDIC, 2025), https://www.fdic.gov/analysis/2025-risk-review.pdf

Aditya Soni and Deborah Sophia, “Microsoft to cut about 4% of jobs amid hefty AI bets,” Reuters, July 2, 2025, updated July 2, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/world-at-work/microsoft-lay-off-many-9000-employees-seattle-times-reports-2025-07-02/

Danielle Abril, “The nation’s largest employers are putting their workers on notice,” The Washington Post, November 1, 2025, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2025/11/01/layoffs-workers-ai-amazon-walmart/

Charts on data center buildout bottleneck:

MSCI Real Assets, via JPMorgan Chase. Chart reproduced in Christopher Mims and Nate Rattner, “When AI Hype Meets AI Reality: A Reckoning in 6 Charts,” The Wall Street Journal, November 14, 2025.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Average Price: Electricity per Kilowatt-Hour in U.S. City Average (APU000072610),” FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, accessed November 23, 2025, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/APU000072610

“Supreme Court justices appear skeptical that Trump tariffs are legal,” CNBC, November 5, 2025, https://www.cnbc.com/2025/11/05/supreme-court-trump-trade-tarrifs-vos.html (accessed November 5, 2025).

Tom Balmforth, Max Hunder, Prasanta Kumar Dutta, Sumanta Sen, Sudev Kiyada, and Mariano Zafra, “Inside Ukraine’s Drone Campaign to Blitz Russia’s Energy Industry,” Reuters Graphics, October 16, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/graphics/UKRAINE-CRISIS/RUSSIA-ENERGY/gdpzbxkgwpw/

Associated Press, “After a stop in Cuba, 2 Russian ships dock in Venezuelan port as part of ‘show the flag’ exercises,” AP News, July 2, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/venezuela-russia-navy-ships-cuba-d594c7c8fc97a903e5dc90754970b8c0

Another Deepseek moment charts:

Hong, Kyungju, Yulin Liu, and Jie Shun Yeow. “DeepSeek dethrones ChatGPT, Nvidia crashes - Market Insights (January 2025).” Endowus Insights. Published February 18, 2025; updated April 9, 2025. https://endowus.com/insights/endowus-market-insights-jan-2025

The ATOM Project, “Model Adoption by Region — Global Regional Model Adoption by Month (Nov 2023–Sep 2025),” The ATOM Project (American Truly Open Models), accessed November 2, 2025, https://www.atomproject.ai/. (Data source noted on page: Hugging Face Hub.)

Move to hard money charts:

BofA Research Investment Committee (RIC), “Exhibit 25: Central Banks Are in Their Longest Gold-Buying Spree,” in The RIC Report (Bank of America Global Research, October 2025), using Bloomberg data.

Bruno Venditti, “Central Banks Now Hold More Gold Than U.S. Treasuries,” Visual Capitalist, October 8, 2025.

Military escalation and control of trade lanes charts:

Jonathan Saul and Helen Reid, “Red Sea Trade Route Will Remain Too Risky Even After Gaza Ceasefire Deal, Industry Executives Say,” Reuters, January 17, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/red-sea-trade-route-will-remain-too-risky-even-after-gaza-ceasefire-deal-2025-01-17/

Matthew P. Funaiole and Brian Hart, “China’s Military in 10 Charts,” Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), September 2, 2025, https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-military-10-charts, accessed November 1, 2025.

Mike Fredenburg, “Why Russia Is Far Outpacing US/NATO in Weapons Production,” Responsible Statecraft, August 14, 2024, accessed November 1, 2025, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/russia-ammunition-ukraine/

Monetary and balance sheet charts:

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Federal government current expenditures: Interest payments (A091RC1Q027SBEA)” and “Federal Government: National Defense Consumption Expenditures and Gross Investment (FDEFX),” retrieved via FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, accessed November 1, 2025, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/A091RC1Q027SBEA and https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FDEFX

Peter G. Peterson Foundation, “Our National Debt,” accessed November 21, 2025, https://www.pgpf.org/our-national-debt.

Monetary and balance sheet strength table supporting data:

Alfani, G. & Ammannati, F. (2017). Long-term trends in economic inequality: the case of the Florentine state, c. 1300–1800. The Economic History Review, 70(4), 1072–1102. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45183403

Putnam, Lane F. “The Venetian Money Market: Banks, Panics, and the Public Debt, 1200–1500.” ResearchGate, 2014. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269643384_The_Venetian_Money_Market_Banks_Panics_and_the_Public_Debt_1200-1500

Cruÿssen, N. (2016). “Four Hundred Years of Central Banking in the Netherlands, 1609–2016,” in Sveriges Riksbank and the History of Central Banking. Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/sveriges-riksbank-and-the-history-of-central-banking/four-hundred-years-of-central-banking-in-the-netherlands-16092016/FFE0331A290CF44FE65C33F04B6B0E40

Office for Budget Responsibility. (2023). 300 years of UK public finance data. https://articles.obr.uk/300-years-of-uk-public-finance-data/index.html

U.S. Office of Management and Budget and Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Federal Debt: Total Public Debt as Percent of Gross Domestic Product (series GFDEGDQ188S), FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, accessed July 14, 2025, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/GFDEGDQ188S

U.S. Department of the Treasury, Bureau of the Fiscal Service, Statement of Social Insurance, Fiscal Year 2024 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Treasury, Bureau of the Fiscal Service, February 2025), https://www.fiscal.treasury.gov/files/reports-statements/financial-report/2024/social-insurance.pdf

U.S. Government Accountability Office, Financial Audit: FY 2024 and FY 2023 Consolidated Financial Statements of the U.S. Government, GAO‑25‑107421 (Washington, DC: January 16, 2025), https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-25-107421.pdf

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “Federal Debt: Total Public Debt as Percent of Gross Domestic Product (GFDEGDQ188S),” FRED, accessed July 15, 2025, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/GFDEGDQ188S

“Financial cost of the Iraq War,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Financial_cost_of_the_Iraq_War (accessed July 15, 2025)

Richard Baldwin, “China is the World’s Sole Manufacturing Superpower: A Line Sketch of the Rise,” VoxEU (Centre for Economic Policy Research), January 17, 2024, accessed November 1, 2025, https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/china-worlds-sole-manufacturing-superpower-line-sketch-rise

Our World in Data, “Electricity generation (TWh),” interactive chart using data from Ember (2024) and Energy Institute, Statistical Review of World Energy (2024). Accessed November 1, 2025. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/electricity-generation?tab=chart&stackMode=absolute®ion=China~United%20States

Technological innovation chart:

AI Index Steering Committee. AI Index Report 2025, Chapter 1: Research and Development. Stanford, CA: Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI (HAI), 2025. PDF, https://hai.stanford.edu/assets/files/hai_ai-index-report-2025_chapter1_final.pdf (accessed November 1, 2025).

Cultural and institutional cohesion data and charts:

Pew Research Center, “Public Trust in Government: 1958–2024,” Pew Research Center – Politics & Policy, June 24, 2024, accessed November 1, 2025, https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2024/06/24/public-trust-in-government-1958-2024/

Gallup, “Trust in Media at New Low,” Gallup News, October 2025, accessed November 1, 2025, https://news.gallup.com/poll/695762/trust-media-new-low.aspx

American National Election Studies (ANES), “Affective Polarization of Parties: Own-party and rival-party feelings, 1978–2024,” The ANES Guide to Public Opinion and Electoral Behavior, accessed November 1, 2025, https://electionstudies.org/data-tools/anes-guide/anes-guide.html?chart=affective_polarization_parties

Nuclear power as a case study in hegemony charts:

Shangwei Liu, Gang He, Minghao Qiu, and Daniel M. Kammen, “China reins in the spiralling construction costs of nuclear power - what can other countries learn?” Nature (Comment), July 28, 2025, doi:10.1038/d41586-025-02341-z.

Our World in Data, “Electricity generation (TWh),” interactive chart using data from Ember (2024) and Energy Institute, Statistical Review of World Energy (2024). Accessed November 1, 2025. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/electricity-generation?tab=chart&stackMode=absolute®ion=China~United%20States

Xinhua, “China Achieves Thorium-Uranium Nuclear Fuel Conversion in Molten-Salt Reactor,” November 1, 2025, https://english.news.cn/20251101/5fd1cf3dab394e9eb6dc69777ed1577d/c.html

World Nuclear Association, “Thorium,” updated May 2, 2024. https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/current-and-future-generation/thorium

Oak Ridge National Laboratory, “History | Molten Salt Reactor.” https://www.ornl.gov/molten-salt-reactor/history. Accessed November 2, 2025.

Brian Blackader, Eric Buesing, Jorge Amar, and Julian Raabe, “The Contact Center Crossroads: Finding the Right Mix of Humans and AI,” McKinsey & Company, March 19, 2025, https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/operations/our-insights/the-contact-center-crossroads-finding-the-right-mix-of-humans-and-ai, accessed November 2, 2025.

Pierre DeBois, “Call Center Statistics That Matter: What Customers Expect in 2025,” CMSWire, July 18, 2025, https://www.cmswire.com/contact-center/16-important-call-center-statistics-to-know-about/, accessed November 2, 2025.

King White, “Site Selection Group Releases 2025 Global Call Center Location Trend Report,” Site Selection Group Blog, March 17, 2025, https://info.siteselectiongroup.com/blog/site-selection-group-releases-2025-global-call-center-location-trend-report, accessed November 2, 2025.

“50 Revealing Call Center Statistics & Trends (2025 Update),” Passive Secrets, September 9, 2025, https://passivesecrets.com/call-center-statistics-and-trends/, accessed November 2, 2025.

Dan Milmo, “Leading Law Firm Cuts London Back-Office Staff as It Embraces AI,” The Guardian, November 21, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2025/nov/21/increased-ai-use-law-firm-clifford-chance-cuts-london-jobs-10-per-cent

Hugh Son, “Here’s JPMorgan Chase’s Blueprint to Become the World’s First Fully AI-Powered Megabank,” CNBC, September 30, 2025 (article noted here), and eFinancialCareers, “JPMorgan’s New Plan to Cut Junior Bankers & Shift Jobs…,” October 3, 2025.

Job losses showing up in macroeonomic data charts:

Gad Levanon, Matt Sigelman, Mariano Mamertino, Mels de Zeeuw, and Gwynn Guilford, No Country for Young Grads: The Structural Forces That Are Reshaping Entry-Level Employment (Burning Glass Institute, July 2025), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/6197797102be715f55c0e0a1/t/68fa5bb9f727046443900bc4/1761237945960/No%2BCountry%2Bfor%2BYoung%2BGrads%2BV_Final7.29.25%2B%281%29.pdf

Prometheus Research, “Where Are We in the Business Cycle?” The Observatory (Substack), June 10, 2025, https://www.prometheus-macro.com/p/where-are-we-in-the-business-cycle.

Allie Kelly and Madison Hoff, “5 Charts Show Why Gen Z College Grads Are Hitting the Job Market at the Worst Possible Time,” Business Insider, June 21, 2025, https://www.businessinsider.com/charts-gen-z-college-grads-job-market-hiring-unemployment-2025-6, accessed November 1, 2025.

Prior industrial revolutions table supporting data:

Allen, Robert C., The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective, Cambridge University Press, 2009

U.S. Census Bureau, Historical Statistics of the United States (1975), Table D832

John, Richard R., Network Nation: Inventing American Telecommunications, Belknap Press, 2010

Gordon, Robert J., The Rise and Fall of American Growth, Princeton University Press, 2016

Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment and Earnings, 1909–2015,” and U.S. Census Historical Tables

OECD, Internet Access and Usage by Individuals, 2013

Manyika, James et al., Jobs Lost, Jobs Gained: Workforce Transitions in a Time of Automation, McKinsey Global Institute, 2017

Nicholas Felton, “Consumption Spreads Faster Today,” graphic for the NYT op-ed by W. Michael Cox and Richard Alm, Feb. 10, 2008.

Talia Goldberg and Bhavik Nagda, “AI Escape Velocity: A Conversation with Ray Kurzweil,” Bessemer Venture Partners - Atlas, March 11, 2024, https://www.bvp.com/atlas/ai-escape-velocity-a-conversation-with-ray-kurzweil, accessed November 2, 2025.

Tony Seba (RethinkX cofounder) slide deck (APTA, 2018): Rethinking Transportation 2020–2030: Disruption, Implications & Choices (slides 2–3). The deck credits the originals: “US National Archives: Fifth Ave NYC on Easter Morning 1900” and “George Grantham Bain Collection, Photo: Easter 1913, New York. Fifth Avenue looking north.”

Olds Motor Works, “The Passing of the Horse” (advertisement), 1903. Scan hosted by The Old Car Manual Project, Oldcaradvertising.com, https://oldcaradvertising.com/Oldsmobile/1903/1903%20Oldsmobile%20Ad-01.jpg (accessed November 2, 2025).

Re-employment rate assumes a one-year lag, applied directly to the people laid off in prior year; regulatory reaction ranges applied variably depending on which AI technology S-curve.

Daniel Oliver, “The Fed Begins to Ease,” Myrmikan Research, May 10, 2019, p. 4 (chart: “Gold Price in Weimar Marks [1914=1]”), https://www.myrmikan.com/pub/Myrmikan_Research_2019_05_10.pdf, accessed November 2, 2025. myrmikan.com

GPTs are GPTs. https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.10130

What if the real scarcity of this century is not data, talent or capital –

but epistemic integrity?

Over the last years, rare intuitive minds from Asia, the Nordics, the DACH region and elsewhere have approached me with the same intuition:

“We want to build aligned local solutions based on epistemic-integrity frameworks – Sapiopoiesis, Sapiocracy, Sapiognosis – but without diluting or instrumentalising them.”

They are not trend-seekers, but potential enablers of the world to come.

They are what I call Minds of Integrity: polymathic minds who would rather lose opportunities than betray coherence, and who treat Sapiopoiesis as a serious civilisational hypothesis, not as a metaphor.

From these parallel conversations, a new structure is now emerging:

The Epistemic Integrity Umbrella –

an emergence centre for Sapiopoietic initiatives and Minds of Integrity.

Its organic purpose is simple and demanding:

- to hold a clear source and custodian for the Sapiopoietic architecture,

- to define a non-mutation principle that protects these concepts from tactical hollowing-out,

- and to offer a recognisable horizon for initiatives that want structural alignment rather than another slogan.

It is not an organisation in the usual sense of redundancy management – it is an orientation layer.

Those who enable it do not submit to a brand, they connect to a source that keeps their own work ethical, intelligible, defensible and non-trivial.

If you are someone whose practice has already forced you into a higher standard of integrity than your environment – and you are responsible for decisions in education, AI, governance or institutional design – and you feel that our systems are over-informed and under-oriented, this may concern you more than any new tool or framework.

The foundational essay, “Designing the Epistemic Integrity Umbrella”, is now live on Epistemic Futures.

Link in the comments.

#EpistemicIntegrity #Sapiopoiesis #EpistemicFutures #CivilizationalDesign #AIandSociety